Punk is often portrayed as an aggressive movement started by a small group of people who were disenfranchised with the world in which they grew up in. They were unimpressed and unmoved by the music, fashion and ideals of the day. So they forged ahead with their own culture that reflected and voiced these issues, and subsequently prospered in a climate that rewarded creativity and productivity above all else.

In reality, it is not that simple. Marketing strategies and major record companies undeniably helped push the scene forward, as it grew into a worldwide commodity from the mid 1970s onwards. It was capitalised on, having come from a place in many circumstances that was ill-fitting of the backstory that was generated around the punk scene at the time. As critic Patrick West stated, “Government and corporations have always controlled art, and it’s naïve to think that this was a new phenomenon. One of the best things that punk did was to draw our attention to this historical norm so starkly.”

All of this is not to dismiss punk rock’s importance in the history of music though. It may have been short-lived and manufactured at times, but it remains a fluid genre to this day, a key influencer on the music that was created for decades to come – music that brought about the rise of the independent music maker and the independent youth. It broke the status quo within the music industry that had dictated the taste of the youth for too long, and opened up a new set of rules that generations in the future would come to live by…

“Bill Grundy was yesterday suspended by Thames Television for two weeks after being accused of ‘sloppy journalism’. Mr Grundy later responded, ‘all I was trying to do was prove that these louts were a foul-mouthed set of yobs.”

This extract from the Guardian in 1976 refers to the now infamous appearance of the Sex Pistols on the Today Show, which was hosted by Grundy himself. It was a first taste for many of the upcoming onslaught that ‘punk’ would bring to England, and indeed worldwide. In it, the host exchanged barbs with guitarist Steve Jones where he dared him to say something “outrageous.” Jones replied by ranting at Grundy and showering him with expletives. Before the incident, punk existed on the margins, safely kept underground and away from the masses. It was still a year before the Pistols’ released their debut, but they were now firmly in the public consciousness.

If any band has become a poster for the punks, it is the Sex Pistols. They arrived with an image of bad behaviour, intolerance for the government, a leering hatred for the so called establishment, and a severe case of injustice. A great example of this is from their TV appearance where they utilised the reputation they had in the underground and strengthened their image as non-conformists live on the BBC for the whole nation to see.

To understand why this appearance had such a profound impact on the public though, is to first recognise the merits of the “shock effect.” Neil Eriksen in his case study entitled “Popular Culture and Revolutionary Theory: Understanding Punk Rock” wrote,

“A song serves to generate leisure effects by creating an avenue for escape into apathy and fantasy. But a song can also have another effect; it can serve to orient the listener to a ‘critical response … in the sense that he or she will be provoked into thinking and questioning by it.’ One way that such critical orientation can be affected is through the shock effect of jolting the audience out of the more passive habitual response.”

This is primarily what punk rock sought to do both through its actual music and its image. The Sex Pistols (also see GG Allin for a more explicit case) played on it constantly to antagonise their audiences, all the while building up a cult following. The band, however, were not exactly as they seemed. As has now been very well documented, they were an extension of manager Malcolm McLaren’s vision, whose day job was selling “fetishistic clothing daubed with slogans” from his London store SEX, along with legendary designer Vivienne Westwood. In a way, the band were a vehicle for this as they captured the imagination of the disaffected youth, ready for something new and wild. Sid Vicious, the bassist who couldn’t actually play bass, was the most obvious component of it all. He was purely in the band due to his aesthetic and attitude, helping to propel and sell the image of the ‘punk’ to everyone else.

Barely two years later, the band came to a screeching halt after just one album. Frontman Johnny Rotten famously addressed the crowd during their final gig in San Francisco. “Ever get the feeling you’ve been cheated?” he asked wearily. It was perhaps a pondering of his own fate as well as that of his audience’s.

Punk rock is generally considered to have arrived sometime around the mid 1970s. Earlier bands like MC5 and Iggy and the Stooges had elements of punk in them, but it wasn’t until the likes of the Ramones and Sex Pistols emerged that the scene really began to take off. As observed by an article from CNN, “while ’70s rock gods like Led Zeppelin and Pink Floyd filled their songs with ever expanding guitar solos, The Ramones packed 14 songs in under 30 minutes.” And it was this immediacy that proved to be so enticing for some as short and sharp blasts of music became preferred.

There are varying beliefs on what punk rock and its surrounding scene actually was and what it brought to the people who listened to it. According to Stuart Home in his piece “Cranked Up Really High“, “What punk did do was tap into a reservoir of social discontent and create an explosion of anger and energy. Punk wasn’t offering a solution… It was pure sensation, it had nothing to offer beyond a sense of escape from the taboo of speaking about the slimy reality of life as the social fabric came apart.” Meanwhile, Tim Patterson was quick to dismiss it in his 1977 article entitled “Punk Rock Reflects Cultural Decay” where he described it as a “social disease… It is a part of the manipulation business and… the crudest cultural hoax in decades.” Regardless of its term though it unquestionably ignited a certain part of youth culture and drove them to find their own voices within society.

Time Magazine touched on this when it stated that, “Punk began with a feeling of frustration and rage and turned it into an idea that could be acted upon. Employing deconstruction and self-starter empowerment — the DIY ethic — it liberated a generation to create its own culture.”

The arrival of punk both in the UK and in America took the music industry by surprise as it quickly imposed its will. The number of small record labels that started up during the early stages of punk’s rise was impressive, but was in part due to major record companies not being able to adapt in the face of change. Punk capitalised on this and took advantage of large record companies being blind sighted as they shovelled their money into new recording technologies, while believing they still controlled the popular and youth cultures. Kevin Dunn points out that this “meant that older studio equipment and studios suddenly became available for independent music producers and companies to either buy or rent at affordable costs.”

The Buzzcocks became the makers of the first British homemade record directly as a result of this. Their Spiral Scratch EP was made after the band borrowed $1,000 from their families to record and release it. As a result of this newfound opportunity, many small labels began to distribute their own albums through independent retailers. An expanding business was quickly established as fans came to rely on these lesser known labels to get them onto the up and coming punk bands from around their area. Punk music essentially creating a separate branch of recording, pressing and distributing away from the major music companies. It wasn’t only in the UK that this was occurring though, as around the world people involved in punk music saw the opportunities that were suddenly available in the music industry. “Often grounded by local DIY record labels that had been inspired by the initial outpouring of U.K. punk labels- the Los Angeles punk scene from 1977–79 embraced the DIY ethos too.”

In order to initially attract customers to their products, small labels devised marketing strategies that allowed them to operate with a profit. Fan newsletters were drafted up that people could subscribe to in advance and they were then sent a number of limited edition records that were marked as ‘exclusives’. “The do-it-yourself aspect of the production and packaging spoke for itself. We created ideas for affordable products which set the pace for imitators, like the clear plastic-bag 45 sleeves and the multi-colour silkscreened picture disc,” small label owner David Brown recalled.

However, what started out as a small community soon grew into an untapped commodity. The small labels were thriving in the punk rock scene and major labels finally cottoned on to its marketability and earning potential. A new market was available to them that was almost entirely related to the youth of the decade. Major labels began to sign up every punk band they thought they could make money from. The Sex Pistols were the first signed in the UK, contracting with EMI in 1976.

As Dunn noted, “by 1978, most of the best known U.K. punk bands had been signed by major record labels. Generation X and Stiff Little Fingers went to Chrysalis, the Vibrators signed with CBS, Siouxsie and the Banshees and Sham 69 signed to Polydor, the Undertones and the Rezillos went to WEA. While the flag-bearer of the DIY record label movement, the Buzzcocks, signed to United Artists.”

Major labels then took the initial marketing tools devised by small labels to attract buyers and multiplied it by 1,000. Gimmicks suddenly became the new norm on how to release and sell punk rock records. “Limited editions, coloured vinyl, picture bags, 6 inch singles, 12 inch singles, 10 inch albums, 45 rpm ‘albums’, scratch ‘n’ sniff sleeves etc. etc. was the sign of punk rock,” according to Home. “It proved of supreme importance to the corporate entertainment industry as an exercise in marketing research and development.” And in many ways this compromised the integrity of not only the band but also the music which they were making. What had started out as a small-time thing became just another cog in the music industry machine.

“They said we’d be artistically free, when we signed that bit of paper. They meant, let’s make a lot of money, and worry about it later.”–The Clash Complete Control lyrics.

The punk rock movement displaced heavy rock that had begun to sink into indulgence by the midway point of the decade. It was an adrenaline shot that aimed to destroy everything in sight. A dirty and aggressive reaction by a group of youths who were sick of all that had become before them. The bands played on the societal pressures and problems of the time after they had initially captured the public’s imagination. In the case of most English bands, it was a working class response to oppression and unemployment.

But from the start it had conflictions within its main framework. In most cases, by the end of the decade major labels controlled bands and had them signed to lucrative contracts, which took them out of the situations that they seemed to draw on at their inceptions. Some bands were simply a product of ulterior motives, while others jumped on the popularity of the scene just in order to make money. Until,in the end, it seemed to be a manufactured movement that was controlled with a vice-like grip by major companies just like all that had gone before them.

Despite this though, punk rock is still responsible for a number of high points in music history. It spawned historic places like CBGB’s in New York where the punk scene first exploded with bands like Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers and the Ramones making it their home. While it also influenced the next wave of musicians in the post punk genre that spawned bands like Joy Division and The Cure. Most importantly though, punk rock made it seem like just about anybody was capable of being in a band. It brought in the first batch of independent music makers and distributors that broke the monopoly of major labels. With the effects of which are still being felt three decades later.

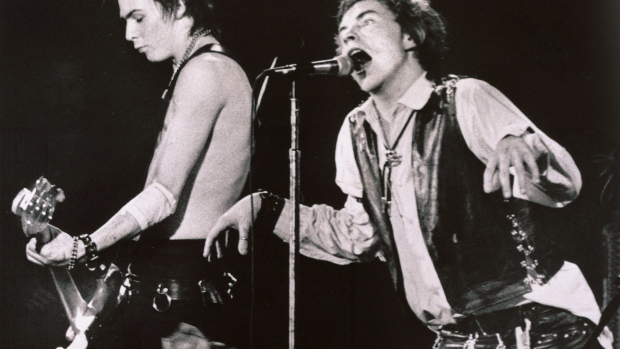

Image: CBC/AP