Billed as the final studio album of Jay Z, 13 years and 5 albums later, any retrospective of the The Black Album simply has to be examined through the lens of this clever marketing ploy.

Writing in 2017 as a member of a sophisticated consumer public who has lived through countless faux-John Farnham retirements, it’s difficult to imagine that people in 2003 genuinely believed that this would be Hova’s last album.

However both the public and critics alike might be forgiven for falling for such an obvious sales tactic given the seeming sincerity of the gesture. The album is littered with misty-eyed references to retirement and the closing chapter of the Jay Z story. On December 4th Jay Z tells his audience they may not truly know what they’ve got till it’s gone – “maybe you’ll love me when I fade to black.” The hook in Moment of Clarity cleverly links the titles of Jay Z’s prodigious body of work, noting his “Blueprint beginning to that Black Album ending.” The strangely melancholic Allure shows a rare vulnerability in the typically braggadocios MC. Hov is practically teary-eyed when he listlessly sighs “shit, I know how this move ends, still I play, the starring role in Hovita’s Way.”

In fact, many contemporary critics noted that whether or not The Black Album really was Jay Z’s final album was irrelevant. Regardless, the album is thematically fixated with the concept of closure and resolution. From the unique perspective of looking back on his career, Jay Z is magnanimous, honest and raw. Jay Z has always been hip-hop’s Philosopher-King, but the Black Album comes from a place of true enlightenment. The pettiness that is the sad staple of all gangsta rap is stripped bare here. Previously the mastermind of gold standard diss track The Takeover, a lofty Hova instead dismisses his nameless competitors on Dirt off Your Shoulder and What More Can I Say? The end of Jay Z’s career gives him a unique ‘Moment of Clarity’ – no longer the embittered hustler, Jay Z is finally able to forgive his heroin addict father; “save a place in heaven till the next time we meet forever.”

Upon the release of The Black Album in 2003, you could practically hear the cacophony of critics, a mournful lament that not only did it “show Jay Z at his very best, it showed that he was getting even better.” Only now are we beginning to confront the concept of the ageing hip-hop Titan, what with most of the genre’s living heroes pushing 40 or more. Once the voice of disaffected youth the world over, the cartoonish voices Eminem had performed for decades felt strangely feeble on The Marshall Mathers LP 2. In the long road to completing Tha Carter V, Lil Wayne has been beleaguered with health scares and political controversy. Yasiin Bey (Mos Def) just released what Pitchfork described as “by far the worst thing he’s ever released.” Biggie and Tupac are legendary because they died young, before they had a chance to age, wane in skill, and generally make poor career choices. People might think very differently if in 2016 a 400 pound Biggie Smalls was putting out his 9th studio album out via Mailchimp with three Skrillex features and several accompanying apps.

Hip-hop is a culture deeply connected with bravado, dissidence and youth. It’s rare for a rapper to choose to make a final album – the marketplace will generally make that decision for you (think: 50 Cent). The Black Album is rare in that it allows Jay Z to go out on his own terms, guns blazing. The worlds of Coppola and Scorsese are littered with canny gangsters who have no choice but to pull off one last perfect heist before they abandon the life of crime for good. Of course, the big grab is always challenging, dangerous and in the end, always elegantly executed. There’s little surprise that Jay Z, the Frank Lucas of rap, also wanted his final score to be risky yet flawless. Jay Z chooses to go out with a bang, and not with a whimper. He’s quitting while he’s ahead: “Jay’s status appears to be at an all-time high,” he wheezes on the Roots-esque live jam Encore, “the perfect time to say goodbye.”

Gangsta rap is a genre that I love so dearly that it has seeped into me on a molecular level. Nonetheless, it still never fails to appal me for its mind-blowing repetitiveness. While underground rappers have experimented with narratives and perspectives, hip-hop on the whole is only ever concerned with two things – rising from poverty and then living a lifestyle of sickening decadence. It is without doubt the most overplayed theme in all kinds of music ever – possibly even more than the theme of falling in love. But nobody does this simple trick better than Jay Z. Of course, the most brilliant thing about the ‘last album’ angle is that it makes this repetition completely justifiable. This is a retrospective. A recap on his life and career. And any kind of reflection is inherently going to involve a discussion of how he rose from poverty to sickening decadence. The Black Album is a 55-minute flashback episode. Like a home movie, it has a nostalgic feel to it. And Jay Z is right. We will miss him when he’s gone. Whilst it might be repetitive, let’s enjoy this brief replay, because there truly may never be anything better again.

Although an actual sequel to Jay Z’s canonical The Blueprint was released as early as 2002, The Black Album is its true successor in every sense. The Black Album breaks few barriers, instead preserving the status quo set by Jay Z himself only 2 years before. But I’ve misspoken. Because The Blueprint is so much more than just the ‘status quo,’ it is a 15-track offering that epitomises and encapsulates the entire genre; the benchmark, the apex, and the high-watermark of rap. Should fans be satisfied with such obvious repetition?

It’s an obstacle that Kendrick Lamar similarly encountered in 2012. What do you do when your unofficial bootleg EP is so perfect, that it is bound to eclipse anything that you could possibly create with a record label, money and a team of producers behind you? The Interscope-produced Good Kid, m.A.A.d City is largely a regurgitation of the independent Section 80. But this was so much more than cheap imitation. Hip-hop was left with two masterful cuts from the same cloth. Like Elmyr de Hory, sometimes there is greater skill in executing a perfect replica than a weak original.

If The Blueprint was not broken, than Jay Z did not try to fix it with The Black Album. And if you have the formula, the recipe, the very blueprint for perfection in your hands – than why not recreate it time and time again?

The Black Album follows the formula set by The Blueprint to its very step. Jay Z’s army of producers carefully copy the crisp bold sound that made The Blueprint so fucking listenable – 70’s soul samples, with clean, vibrant drums. The Black Album has The Blueprint’s appetite for vigour and warmth. Arguably, The Black Album refines the recipe to produce something slightly more brittle, dark and dangerous.

There’s no doubt that no one tells the ‘rags to riches’ story better than Jay Z. Having memorised every line, he has little interest in deviating from the script. “I got a hustler’s spirit, n*gga, period,” he says on Public Service Announcement. If only Jay Z was always this concise. Remarkably, Jay Z would go on to recycle this same story again and again over another four studio albums – with no possible end in sight.

The fact of the matter is that Jay Z’s second, even third best attempt, is still so much better than anything offered by any of his 2003 contemporaries. And even if it’s only a shadow of The Blueprint, well, even a shadow of the Eiffel Tower is better than the actual Federation Square.

Of course it’s no secret that the God MC is only as good as the mortal producers who toil to build his pyramids. Like the Olympics, a Jay Z record is always an assembly of the world’s best producers, showcasing their talent on a much larger platform than they could ever enjoy independently.

Of course all kudos must begin first with Jay Z who struggled to hip-hop supremacy and then lit the beacon that would call forth the world’s best beatmakers. But by 2003 Jay Z had first dibs on the finest cuts produced globally – the offal left to 50 Cent or Lil Wayne. In fact The Black Album was originally marketed as a 12-track affair, with each song produced by a different world-class producer. This gimmick was unworkable and quickly abandoned, but the message stood: Come forth, come forth ye great producers of this Earth and lay your offerings before the feet of the King. And when Just Blaze, Rick Rubin and the Neptunes are all falling over themselves to provide you with music – hell, even the Soundcloud rappers from your hometown could put out a Billboard top 40 track.

The overall feeling of The Black Album is steered by Blueprint veteran beatmakers Just Blaze and Kanye West, who occupy almost one third of the album. Their use of soul samples and bold vibrant beats infect The Black Album with the magic of that earlier work. Timbaland is perhaps the only producer who does not conform to the Blueprint mould of the holistic fleshy sound. His wavering synthesiser on Dirt off Your Shoulders has a piss-weak insipid Fruity Loops feel to it. In 2016, with our love of banging and twirling trap drums, it’s hard to believe this song ever passed for a ‘club banger.’ Pharrell’s Neptunes do what they do best on Change Clothes, creating saccharine funk with warm melodies and Williams’ recognisable crooning falsetto.

Eminem’s Moment of Clarity is often derided by critics as a lazy mash-up of the Renegade and Lose Yourself beats. Notwithstanding this, its darker energy is a welcome change of pace. Moment of Clarity certainly seems far more at home on something called The Black Album than anything produced by the Neptunes, ever. Yet without a shadow of a doubt, it’s the inclusion of OG beatmaker Rick Rubin that provides the album with its freshest moment. 99 Problems pays homage to the rock-rap heavy metal boombox sound of early 80’s hip-hop pioneered by Rubin himself, and popularised by the Beastie Boys. It’s as if Rubin set out to create the perfect song to be experienced on the ghetto blaster, the sudden burst of electric guitar and cowbell, feel as if some B-Boy has just jacked up the volume for his favourite track without any kind of warning. The fact that Jay Z manages to ride this erratic and raucous beat is a credit to his lyrical dexterity.

While comparisons with The Blueprint are endless, ultimately both albums have the same aim: the future classic. They are truly timeless albums in a sea of dated mediocrity. Clean, crisp and substantive, it is simply mindboggling to believe these albums are 15 years old. The album title itself connects the African-American legacy with the most famous musicians of all time.

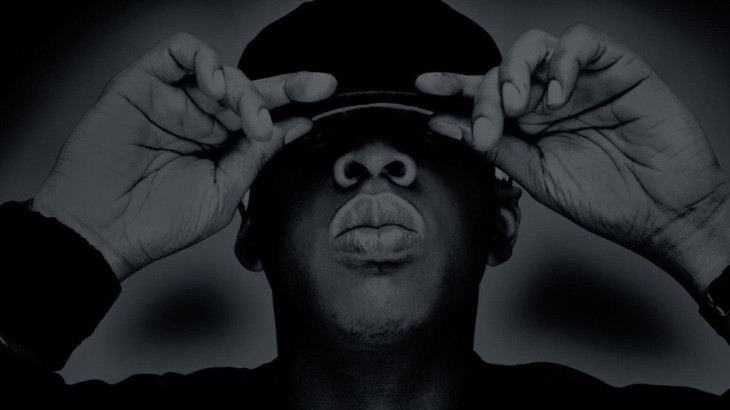

Where The Beatles had their White Album, Jay Z lays claim to a darker but no less significant work of art with his Black Album. In many respects the very reason hip-hop has been so unchanged in over a decade is because it was Jay Z himself who set this benchmark. The paradigm that all rappers have sought to either emulate or blatantly copy. In so many respects The Black Album is a shameless sequel – the Grease 2 of hip-hop. But listeners will not feel exploited. They might feel nostalgia. They will feel reverent, empowered, left in awe by the God MC.