I was in my senior year in high school and coming into my own consciousness as a young’n. I was beginning to take charge of the music I was listening to, what I liked, and what I would rather set my teeth on fire to than endure on some commercial radio show.

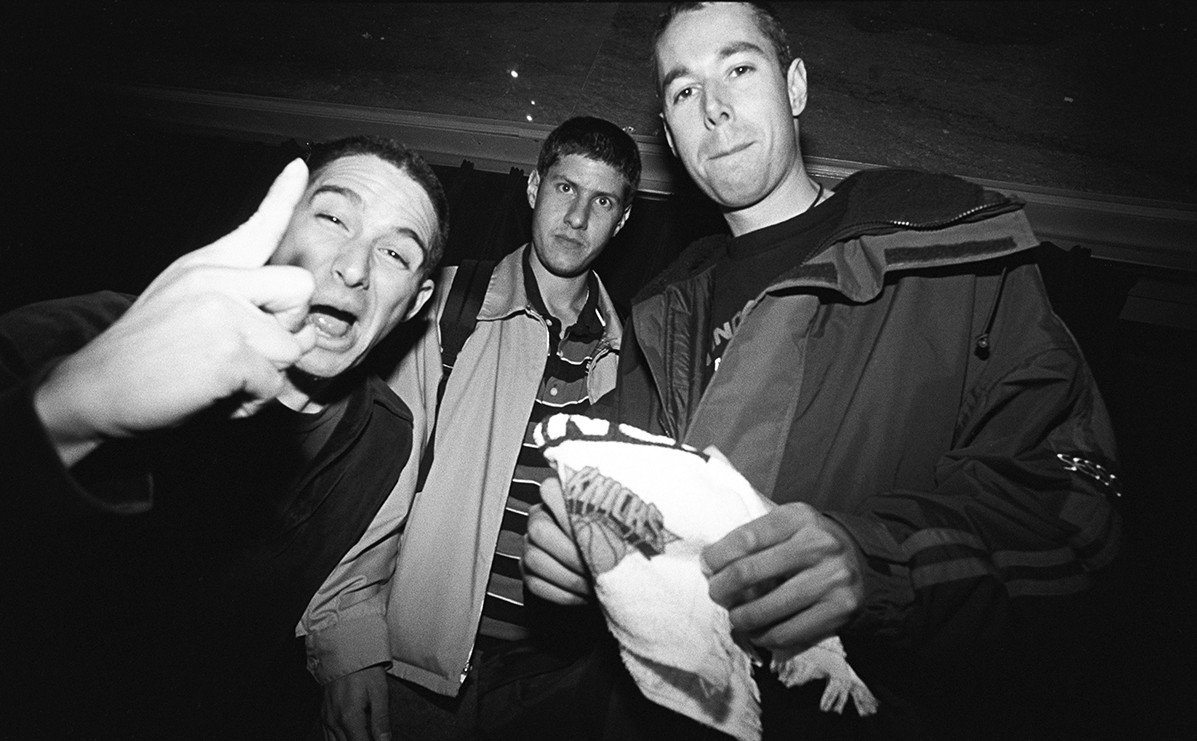

At that time, I had already developed an obsession with bands like AC/DC, Jet, Red Hot Chili Peppers, The Sex Pistols, and The Clash. It was the beginning of my penchant with discovering new music on a regular basis. Although, it wasn’t until I walked into a CD store, when CD stores were still a thing, and I picked up a copy of Ill Communication that my adoration for hip-hop, and three Jewish NYC punks, truly awoke.

Released May 1994, Ill Communication was the The Beastie Boys fourth studio album and their second to reach No.1 on the Billboard charts. It’s regarded as one of their most musically diverse records, drawing from hip-hop, jazz, funk, punk rock and even world music. It nonchalantly fused fast, merciless garage off the back of jazzy flute loops that drove lyrical flows rife with infamous name-drops and feminist undertones. About a decade later, it was my first exposure to the Boys, and I was hooked.

In a genre that is rampant with misogynistic jeers, both in and outside the music, Ill Communication is a refreshing example of the opposite and a departure from their frat boy beginnings. It was not only an opportunity for the Boys to expand upon the live instrumentation they hallmarked in the preceding Check Your Head, but it also announced a looming maturity; one that they embraced in numerous ways.

Their debut Licensed to Ill was a homophobic and misogynistic frat-fest, one that Adrock later formally apologised for, saying “There are no excuses, but time has healed our stupidity.” During Ill, MCA became involved with the Tibetan independence movement and formed a friendship with the Dalai Lama; those Buddhist ties inspiring tracks Shambala and Bodhisattva Vow on the record, featuring enlightened lyrics overlaid to the chanting of Tibetan monks.

Meanwhile, The Update features some of the most socially conscious phrases ever uttered within a Beastie Boys track, where MCA insists that it’s about time we started taking accountability: The Mother Earth needs to be respected/ Been far too long she’s been neglected/ Race against race, such a foolish waste/ It’s like cuttin’ off your nose to spite your face.

On Sure Shot, he also expresses his deeper respect for women: I wanna say a little something that’s long overdue/ That disrespecting women has got to be through/ To all the mothers and the sisters and the wives and friends/ I wanna offer my love and respect to the end. Following his untimely passing in 2012, I tear up every time I hear this.

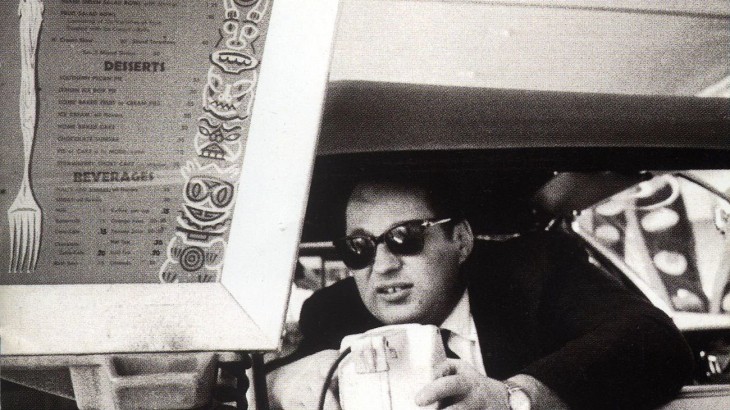

More frequently though, when you bring up the subject of Ill Communication, most people tend to associate it with the instantly recognisable Sabotage. First cab off the rank, it helped to solidify Ill’s success and was accompanied by the now cultish video clip directed by Spike Jonze.

It remains one of their largest roaring rock anthems to date with its non-stop fuzz bassline and stunted, suspenseful verses.

My personal stand-out, though, is Get It Together. In this confounding life of Ranch Legalisation and Pharrell’s headwear, there is nothing unassailably cooler than sampling a 1970’s Moog Machine tune and having Q-Tip rap about Ma Bell over the top. Truly. I learned the lyrics to this seamlessly, with some wannabe Rakim reminiscent flow.

The four of them swap verses like an easy conversation, with the Moog sample slowed down and looped in the back. Q-Tip: “Let me embark on the lyric and the noun and verb.” These guys can be incredibly profound without even trying.

Tough Guy and Heart Attack Man are throwbacks to their Bad Brains-esque roots; speedy, abrasive punk rants that somehow coexist harmoniously with all of the other styles featured on the record. On the former, they’re throwing down some vibe-harshing dude for getting too physical in a pickup basketball game and the latter whiplashing a hefty “good guy” Mike D knows. They’re hilarious, and perfect stand-alone noise tracks.

Numbers like B-Boys Makin’ With The Freak Freak, Do It (ft. Biz Markie), The Scoop and Flute Loop get weird with distorted vocals that are barely discernible, and some even weirder sampling (an ode to the days of tape answering machines). Then there’s the live band element, which is present across the entire album but really comes home on the instrumental tracks; bongos on Bobo On The Corner, funk guitar on Sabrosa, a depressed exotic violin on Eugene’s Lament, and some easy lounge on Ricky’s Theme.

The Beastie Boys completely and utterly surpass their titles as emcees and hip-hop producers, of which they are inarguably pioneers. Ill portrays a vision and finesse that is far more diverse than we could have ever foreseen of the boasting punk kids they premiered as on Def Jam.

Whenever I wanted to feel rad as fuck, or needed some weird inspiration, or if I simply wanted to listen to some funky business, I would put this record on. My friends didn’t understand most of my musical affiliations at that time (not much has changed), and this album is certainly one for the most dedicated connoisseurs of “the dope shit”. I felt as though the Boys were privy to this enormous archive of hip knowledge that I wanted in on, and their music was the secret handshake.

This album appealed to me in a tremendously instinctual way, and was certainly an inspirational precursor to what would become my later work as a photographer. It opened my eyes to how eclectic, freewheeling and boundless music and art could be. There are no rules. Be as weird and unpredictable as you want. If you want to drop samples of French phone conversations, and 1940s stand-up comedy into Moog loops while rapping about freaking beats in blenders over jazz instrumentation and Buddhist chants, no one is stopping you. You just might change someone’s life in the process.

Dedicated to the late, great MCA. RIP.

Photo: Catherine McGann