In much the same way as David Bowie did with Blackstar, you get the sense now that Leonard Cohen’s new album You Want It Darker was always intended to be his epitaph. There was the frank admission in a recent interview about how he had been readying himself for death for some time, the difficult process of crafting his album while he was essentially immobile, and then there was the music itself. A dark lament that featured a scarcity of instruments mixed together in a symbolic stripping back of everything but the essentials. However, while his last album will act as his final statement there is an abundance of poetic verses, love-torn laments, and midnight observations that he left behind.

Although Cohen may not have generated quite the same level of public outpourings of grief that Bowie did when he passed away on Friday at the age of 82, there is no doubting his quality and influence. He was, after all, one of the few men who Bob Dylan championed as a song writing genius.

“As far as I’m concerned,” he was reported as saying once, “Cohen is number one. But I’m number zero.”

Cohen grew up in Westmount, Quebec before his literary ambitions took him all around the world. The likes of New York City and London were taken in. But none of them captured him quite like the Greek island of Hydra did. He withdrew there and progressed from a little known Canadian poet into a well-respected author, poet and musician over time.

Using the money he had acquired from his deceased grandmother’s will, Cohen purchased a large three-story villa that acted as both his home and his workplace while on the island. There was no electricity or running water and the rooms were empty from a lack of furniture. It was a place of distinct isolation at times, where he was kept company by kerosene lamps and very little else. But it was the place where Cohen began to emerge as the writer he had always intended to be.

“I was trained in what later became known as the Montreal School of Poetry….We would meet, a loosely defined group of people, and we would read each other poems. We were passionately involved with them. And our lives were involved with this occupation of writing,” Cohen explained to Paul Zollo in 1992.

“We had in our minds the examples of poets who continued to work their whole lives. There was never any sense of a raid on the marketplace- that you should come up with a hit and get out. That kind of sensibility simply did not take root in my mind.”

His most popular single, Hallelujah, came from 1984’s Various Positions. When that was released he’d already completed six albums and had a number of novels and poetry books behind him. But while he had always gained respect from fellow musicians and gathered a cult following since his debut in 1967, Cohen never sold a lot of records. He remained, essentially, fixed on the peripheries.

“For many years, Cohen was more revered than bought,” The New Yorker’s David Remnick wrote in his recent profile of the singer. “Although his albums generally sold well enough, they did not move on the scale of big rock acts.”

Away from the island of Hydra with its many uninhabited houses, horseshoe-shaped harbour, and his muse Marianne Jensen, Cohen took up residence in New York. It was a world away from what he had grown accustomed to over the past decade, and proved to be a difficult time. Jensen, who was a married woman when he first met her, joined him, but their relationship would not last and collapsed amongst a host of infidelities on both sides.

Death of A Ladies’ Man, the infamous album made alongside producer Phil Spector, captured Cohen at the height of his womanising ways, although it was clear it was never going to continue. “My reputation as a ladies’ man was a joke that caused me to laugh bitterly through the ten thousand nights I spent alone,” Cohen once revealed. He would go on to make just two more albums over the next decade as he retreated away from the attention and limelight once more.

On his late 80s classic Everybody Knows he returned to paint a grim picture of a buckling society, as he stated ruefully that everybody knew that “the good guys lost”, that the “scene is dead”, and that the “plague is coming.” The act of self-medication was always on hand to whisk you away from the truth, but in Cohen’s worlds that he constructed this only served to prolong the pain. Everybody may know that you live forever when you’ve done a line or two of cocaine, but his delivery of it left no doubt in the listeners mind that this wasn’t a good thing.

As well as mortality, the concept of isolation was entrenched like creases in an old shirt within Cohen’s lyrics. The imperfection in his character was never dismissed as a reason for his loneliness though. But nor was it relied upon for pity. It instead acted as a counterbalance to the story, allowing him to paint in grey and not just the usual black and white tones.

“I smile when I’m angry, I cheat and I lie, I do what I have to do to get by,” he sang on In My Secret Life. It displayed a deeply conflicted character who could see his flaws yet was unable to change, despite the dire circumstances they found themselves in.

Much of Cohen’s lyrics throughout his career grappled with these sorts of issues- be them religious, ethical or societal. The observations and experiences were filtered through and then discussed with unbelievable honesty and compassion. However, while he was noted for his lyrical proficiency, other elements of his music were often overlooked as a result.

“When people talk about Leonard, they fail to mention his melodies, which to me, along with his lyrics, are his greatest genius,” Dylan said. “Even the counterpoint lines—they give a celestial character and melodic lift to every one of his songs. As far as I know, no one else comes close to this in modern music.”

Noted for his patience in creating a song, years would often pass by as Cohen worked and then reworked different components of a track over and over again. The tireless work illustrating how Cohen viewed writing his songs as a profession. There was no luck or divine inspiration as far as he was concerned. It was all down to the dedication within the craft and submission to the work that yielded the best results.

“I have whole notebooks for lyrics,” he told Zollo. “I’m very happy to be able to speak this way to fellow craftsmen. Some people may find it encouraging to see how slow and dismal and painstaking the process is… But why shouldn’t my work be hard? Almost everybody’s work is hard. One is distracted by this notion that there is such a thing as inspiration, that it comes fast and easy. And some people are graced by that style. I’m not. So I have to work as hard as any stiff, to come up with the payload.”

Painter Chuck Close once declared that “inspiration is for amateurs– the rest of us just show up and get to work.” This mode of thinking aligned perfectly with Cohen’s own stance. The words went from the likes of a back of a cigarette packet and then into a notebook. And once in there, any number of edits were conducted until finally a song reached its own individual sense of completion.

The descent into detail was what differentiated Cohen’s work from many of his contemporaries. It had to be based in truth, but it also had to be constructed inside a world that was built in and of itself. The little details in life gather up to help form a complete picture- without these, worlds within a song can be devoid of these facets that combine to create reality. Life is in the details, and Cohen obsessed over this concept throughout his career.

“You don’t really want to say ‘the tree,’ you want to say ‘the sycamore,’” he explained. “We seem to be able to relate to detail. We seem to have an appetite for it. It seems that our days are made of details… It’s better to not just say ‘I’m watching TV in my room’ but to say, ‘I’m in my room with that hopeless little screen.’ I think those are the details that delight us. They delight us because we can share a life then.”

After another extended period away from the music industry which saw Cohen relocate to Los Angeles and devote himself to Buddhism under the tutelage of Joshu Sasaki Roshi, he returned at the new millennium reinvigorated. The final years of his career saw him at his most productive, as he toured relentlessly and to critical acclaim. While he also released some of his best loved material, like Nevermind.

“They say life is a beautiful play with a terrible third act,” his son and producer of his final record Adam Cohen told Rolling Stone in September this year. “If that’s the case though, it must not apply to Leonard Cohen. Right now, at the end of his career, perhaps the end of his life, he’s at the summit of his powers.”

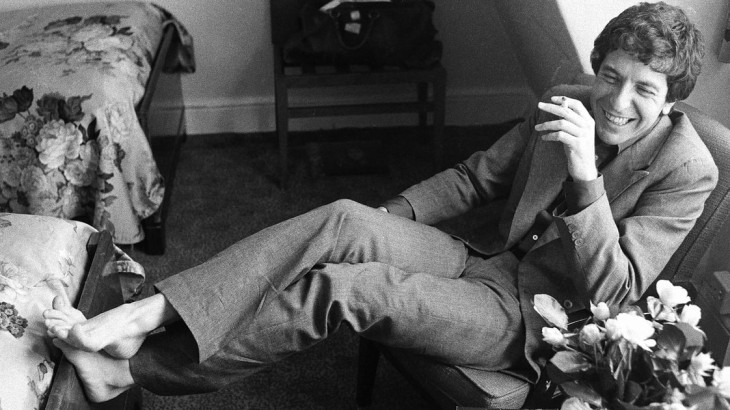

Image: Rolling Stone