Unlike any other genre of music, hip hop has long relied on the somewhat vague and largely intangible concept of authenticity almost as much as it has relied on sonic and stylistic concepts like flow, beat, timing and fashion. ‘Real recognise real’ is one of the more frequent idioms heard uttered by its proponents, a statement that declares as much about the individual saying it as it does the rest of the hip hop community they are directing it to.

Perhaps it’s the gritty, spoken word delivery of hip hop that made realness so important to its early success. Hip hop was power to the people, the voice of the voiceless, the sound a generation of disadvantaged African American youths had been waiting on. When it exploded into the mainstream in the late 80s and early 90s, the authenticity and the realness of its practitioners was tantamount, as they were, in the beginning, highly representative of the people.

Real was when Grandmaster Flash and the Furious Five rapped of broken glass and people pissing on the stairs in the ghetto anthemic The Message. Real was the Notorious B.I.G.‘s rags to riches history laid out so masterfully in Juicy or when Tupac Shakur gave a shout out to his old place of residence at Clinton Correctional Facility at the end of Picture Me Rollin’. Real was N.W.A. and their game-changing documentary on the streets of Los Angeles on Straight Outta Compton. Real was Ice Cube of that group making his fury over the 1992 LA riots heard on The Predator

The other side of the coin, being fake, has also been one of the worst accusations a hip hop artist can be hit with. Eazy-E famously railed against Dr. Dre and his then-protege Snoop Dogg when he called them ‘studio gangstas’ on Real Muthaphuckkin G’z (Dre had been infamously exposed as a make-up wearing former member of pop group World Class Wreckin’ Cru).

Jay-Z and Nas traded all manner of aspersions on each other’s authenticity in their feud to end all feuds. Hell, even B-Rabbit may not have been able to leave Papa Doc speechless in 8 Mile if he hadn’t embraced his own true story as a white trash rapper while simultaneously stumbling across the battle-flipping revelation that Doc was in fact a child of affluence and not the thug life gangsta he was purporting himself to be.

Perhaps the most infamous case of exposed fakery was that of Rick Ross. You’d think most people would take with a grain of salt anything to come out of the mouth of a man who once rapped about his vast cocaine network and, among other ludicrous things, to be owed a hundred favours by the real Noriega.

That didn’t stop the Internet blowing the fuck up in the middle of his feud with 50 Cent, when it was uncovered that Rozay used to moonlight as a Corrections Officer in the 90s, an occupation that might be one step above being a card-carrying Klan member in the eyes of the hip hop community. He’d even jacked his name and look from a real life criminal with an actual cocaine empire and never once credited him for it.

A rare photo of the skeletons inside Rick Ross’ closet

On the flipside you had 50, who made a household name for himself as one of the realest rappers in the game after he went T-1000 on everybody and managed to survive being shot nine (!) times. And yet, despite Fiddy’s assertions that he would send Ross to ‘work at the pizza shop’ when he was through with him, being exposed as a fraud totally didn’t kill his career, and Officer Ricky is still releasing Gold-selling (an actual achievement in the digital era) albums today.

Albeit with less drug empire references and more wearing a chain of himself wearing a chain of himself type of lyrics.

In short, being fake is one of the most frequent accusations made in hip hop but it simply doesn’t have the kind of career-murdering weight one would expect from the comments made by 50 Cent. And even in looking back, was keeping your lyrics strictly in the non-fiction section always strolling hand in hand with success? Hardly.

Who legitimately believed any of the tall tales that were once spread around by hip hop artists? How could you when most of them hid behind a pseudonym in the first place? Even before the dawn of the Internet and its lightning quick capabilities as a fact checker for everything ever, nobody really thought Ice-T killed police officers in his spare time, that the members of the Wu-Tang Clan were an actual gang of psychopathic and violent thugs and not just a bunch of dudes who liked old kung-fu movies, or that Snoop Dogg was actually a practicing pimp.

Pictured: Some bullshit

Sure, it sounded more ‘real’ for your rappers to tackle the kind of drugs, guns and violence tropes that had made the genre so commercially successful, but there was always a kind of unspoken acknowledgement that the story most rappers were telling was not always their own.

It’s the same reason so few people have ever made it a point to call out a contemporary artist like Tyler, The Creator for being fake despite the fact that he has and will absolutely never stab Bruno Mars in his goddamn oesophagus or commit any of the many other atrocities contained in his lyrics. Fewer still called out Eminem as fraudulent for raising all kinds of a shitstorm by doing the exact same thing over a decade earlier.

Both (and many others) have even had tours cancelled and albums boycotted over lyrics which are almost universally recognised as fictional. It’s something that leaves more discerning hip hop fans scratching their heads and wondering how anyone with half a brain in their skull could possibly confuse this art with reality. What conservative moves like these do, however, is to emphasise the sheer impact of lyrics rather than whatever (if any) actual truth is behind them.

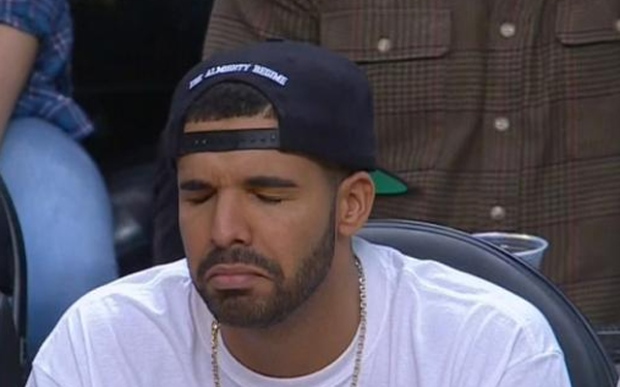

Even though hip hop fans have grown to accept and even embrace the fictional though, the concept of authenticity within hip hop is still present and still important (arguably even more important now than ever), albeit it largely changed. It seems these days that the worst, most inauthentic thing you can do as a rapper isn’t to indulge in your own gangsta fantasy and write songs about things that never happened, but to commit the despicable act of not writing your own rhymes at all. Dr. Dre’s name has been run through the mud time and again over the worst-kept secret in hip hop that he employs a team of ghostwriters. The Internet nearly had a heart attack when it was suggested that Nas used ghostwriters on his Untitled album. Even this latest, utterly laughable feud between Drake and Meek Mill was sparked in part because Mill accused Drizzy of not writing his own raps.

Although does anybody really want to claim responsibility for lyrics like ‘yeah, baby you finer than your fine cousin and your cousin fine’?

The cartoon characters of the hip hop world who boast about the thug lives they lead are still well and truly out there, (see Wayne, Lil; Game, The) but their place on the charts and in the hearts of fans and critics alike, a place they once occupied due to their larger than life personas, has been almost wholly usurped by a new generation of hip hop artists who write their own stories and who tackle relatable, contemporary issues. The violence and criminal activity that hip hop once glorified is being largely overlooked in favour of lyrical themes and artists grounded mainly in reality.

Real now is Frank Ocean having the courage to come out as being gay.

Real now is Childish Gambino rapping about the perils of modern relationships.

Real now is Schoolboy Q acknowledging his daughter whenever and in whatever way he can.

Real now is Run The Jewels speaking out on the riots in Ferguson.

Real now is Kendrick Lamar touching on his battle with depression on To Pimp A Butterfly.

It isn’t the be all and end all key to success to adopt an entirely averse approach to archetypal hip hop fantasy. For all his lunatic lyrical stylings, Tyler, The Creator has a veritable armada of fans at his disposal and you’d still consider rappers like Rick Ross, who wouldn’t have enough truth in his boasts to fill an egg cup, to be successful. Case in point though is Kanye West, whose general statements and levels of self-awareness are usually reserved for evil dictators and people in straightjackets; still the unquestioned ruler of the hip hop (and maybe even the wider) universe today.

Never change

Of the most revered and beloved hip hop artists of today; however, most have embraced, in some form or another, opening up and trying to connect with their fans on a personal level. This is the height of authenticity right now. Where prison walls and threats of bloodshed against his contemporaries may have helped somebody like Tupac’s image in the past, look no further than someone like the recently incarcerated Meek Mill or even the presently-incarcerated Gucci Mane, both of whom are the butt of all manner of jokes despite their circumstances which, were this only a decade or so ago, would have seen them lauded as ‘real’.

If only…

The reality is that image is swiftly giving way to substance and relatability as far as critical and commercial acclaim are given.

We saw this happen with the cold-blooded murder of hair metal at the start of the 90s by grunge music. Grunge represented an utterly resounding rejection of the unachievable excess and opulent flamboyance that hair metal had made a living out of cavorting in for an entire decade. The appeal of grunge was that it was real, that it was down and dirty and that it spoke both to and for a generation of disillusioned youth. Quite the same as hip hop originally did in its first wave.

Artists of the old guard like Nelly, Ludacris, Ja Rule (shudder) and Puff Daddy (or whatever he’s calling himself now) are still around today and are still putting out music, but they’ve come to represent the same kind of over-the-top, gluttonous, alienating fantasy world that bands like Poison and Mötley Crüe came to represent at the end of the 80s and, like them, are largely fading into the background behind this newest wave of ‘real’ artists.

And it’s resulting in music that is of an infinitely better quality.

Authenticity is just as prevalent and just as important in hip hop today, and the most successful artists are the ones who recognise how much the game has changed. Being real isn’t equated with rapping about being some untouchable kingpin of an underworld full of drugs, guns, money and violence anymore, it’s become about being human. We still revere people like Kendrick and Frank Ocean as enormous celebrities, but we celebrate their music because it connects with us in the 21st century.

To be real has become, simply, to be real.