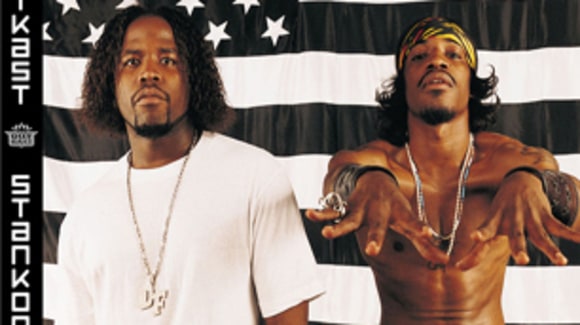

Last month (October 31st) marked the 16th birthday of Outkast’s critically acclaimed fourth album Stankonia. Released as the follow up to Aquemini, the duo of André “3000” Benjamin and Antwan “Big Boi” Patton decamped to their newly purchased studio in Atlanta and came out with a hip-hop hybrid that continued their hot streak. So, how did they redefine the boundaries of the genre while simultaneously becoming leading figures in popular culture?

After making their debuts as two fresh faced hopefuls a year earlier, André and Big Boi arrived at The Source Awards, held at Madison Square Garden’s Paramount Theatre in 1995. There, the imposing Suge Knight, owner of Death Row Records, was in part responsible for an ill feeling plaguing the night, using his stage time to try and recruit artists who were on an opposing label (Bad Boy).

“If any artists out there want to be artists and stay a star, and don’t want to worry about the executive producer all in the videos and all on the records dancing…come to Death Row!” he said.

The New York crowd didn’t take particularly kindly to the obvious jibe aimed at P Diddy and the night descended into hostility. So when the little known Outkast, not affiliated with either and from the South no less, won Best New Rap Group, they were caught up in the crossfire. But amongst all the jeers and uncertainty, Three Stacks was unmoved.

“I’m tired of folks, you know what I’m saying, closed minded folks. The South got something to say,” he declared resiliently.

He would go on to be proven right as Outkast became hip-hop’s most popular and revered group at that time. Their debut Southernplayalisticadillacmuzik had put them on the map, but the three which follows stuck a giant red pin in their location, firmly, and permanently putting Atlanta on the hip-hop map, right there next to New York and Los Angeles.

“It finally gave a clear-cut incision from New York wannabe-ism,” Killer Mike, whose break came on an Outkast feature, explained in ATL: The Untold Story of Atlanta’s Rise in the Rap Game. “It was a great thing that they were handled in that way, because it finally cut the umbilical cord saying, ‘We don’t have to impress you. We’re gonna show you.’”

Following that night they took the ignorance and disrespect in their stride as they attempted to prove that region had no real bearing on the quality of music. ATLiens and Aquemini featured spacey, thematic explorations that floored fans and critic alike. But it was their fourth effort that cemented them as one of the most important and popular artists at the turn of the millennium.

“Stankonia is the sound of every cracked-open door being kicked off its hinges,” critic Mike Driver wrote.

Outkast’s debut album was recorded in a studio known as Bosstown, owned by Bobby Brown. Brown had purchased it in 1991 with the vision that it would become something of a genre-founding hub, similar to Motown Records. Indeed, he saw considerable success from the Bosstown recording booth.

“Me and Dre used to catch the bus up just hoping that we’d see Bobby or somebody who could hear us rap,” Big Boi remembered. “We would never see anyone though.”

Eventually, they were spotted by the production trio of Rico Wade, Ray Murray and Sleepy Brown, also known as Organized Noize. This would be the beginning of a long and fruitful relationship with the trio and the studio. After recording several albums and smash hit singles there, they would purchase the studio themselves from Brown.

“He was like, ‘Hey, man! You can have it!’” Big Boi told The Boston Globe. “But our manager was like, ‘Get out of here. Bobby’s just messing with you.’” When the duo finishing touring and returned home, however, they quickly found out that the studio was in foreclosure. They paid the required money without a second of hesitation and it was officially theirs.

“We then made it into Stankonia,” Big Boi said.

Now afforded the opportunity to spend as much time as they wanted in their newly christened studio, the duo got to work in the spring of 1999. Having produced seven out of the 15 tracks on Aquemini, Earthtone III (Outkast alongside Mr.DJ) joined together again and supplied 13 of the 16 actual songs on the album. It was this familiarity, coupled with an exploding level of creative freedom and desire for expression, that fuelled the album’s sound. They knew what worked, they knew what would get a rise from their fans, but that didn’t stop them from attempting to push the boundaries and experiment – and in turn, that experimentation made their music even stronger.

“We’re just trying to make music for the times,” Andre explained in an interview with XXL Magazine. “We’re trying to show the subculture. People in the streets losing their minds- that’s the tempo.”

A prime example of this was the first single to be taken off the album entitled B.O.B. Over a wailing choir, heavy guitar riffs and apocalyptic drums, both rap about a world that is crumbling down all around them; with reference to then-President Bill Clinton’s bombing of Iraq made in the chorus just for good measure.

Elsewhere, the provocative Gasoline Dreams put the whole of America under the microscope as well as the rest of the world. And while the supposed ‘American Dream’ was burning before everyone’s eyes, there was also the issue of climate change. “I hear that Mother Nature now’s on birth control, the coldest pimp be looking for somebody to hold.”

However, global issues were just the tip of the iceberg when it came to lyrical content as everything from teenage pregnancy (Toilet Tisha) to skewed drug laws were dissected. “My cousin Ricky Walker got ten years doing Fed time on first offence drug bust,” Big Boi raged in Gasoline Dreams.

Along with depictions of drugs taking a hold over the street, and the ensuing violence that was subsequently unleashed, (Spaghetti Junction), there was also room for the massively popular Ms Jackson. Impressively, Three Stacks recorded every single instrument on the song himself, except for the bass. It was the single which would quickly catapult the duo into the heady, previously unfathomable heights of mainstream mega-fame. That it was about a crumbled relationship and the bitter divide that centred on the couples child was not exactly ground-breaking. But the fact that a hip-hop song professed a sense of vulnerability, and extended a genuine apology to those who were hurt, was certainly unique at the time.

“When people pick up the album ten years from now, they can feel what’s going on. It’s a soundtrack of the culture,” André concluded.

The instrumentation flicked around at a chaotic rate. Funk keys a la Parliament provided the bedrock for a few tracks, while heavy guitars more inclined to rock music surroundings fleshed out others. It was a dizzying concoction of sounds, instruments and influences, all flawlessly glued together by lean drum tracks and incredible verses from André and Big Boi.

Explaining the differences in lyrics and flow between the pair, André said, “Big Boi freestyles, I don’t,” he said. “But he’s most definitely Outkast’s anchor. He kind of keeps it grounded.”

The juxtaposition between them is not a new concept. Since their beginnings critics sought to separate the two and assign labels to differentiate them. The “poet and the player” was often what was harkened back to, but on Stankonia this wasn’t always so well defined in the lyrical content.

Instead, the major difference on their fourth album was André’s changing approach to the music as a whole. No longer listening to hip-hop while making the record, focusing instead on George Clinton, Prince and Jimi Hendrix, his delivery began to drift away from that which rap fans may have expected. This experimentation with his vocals and functionality as a rapper actually paving the way for future generations to reap the benefits, who toyed with singing and rapping, as well as unique rhythms and meters.

“Outkast is about personal expression and individualism,” he told The Irish Times. “I can’t force Big Boi to be something he’s not and he can’t change me. That’s the beauty of it.”

One of their crowning musical achievements, Stankonia would sadly be the last time the pair worked so effectively together in the studio. They won the 2002 Grammy award for Best Rap album and sold over four million copies in the meantime, but the surge in mainstream popularity came at an obvious price.

“We do things separately now but it’s a good kind of separation, like an incubation period,” Big Boi explained of their later recording processes.

“The biggest thing that’s changed is that we’re not in the same place at the same time. But we both learned how to write, produce and do the melodic funk thing together. It’s like having two separate cubicles in the same company and meeting in the boardroom to get things right.”

This setup inevitably perished as the years continued, with the two high school friends drifting away from each other and the band over time. But while their union (kind of) ended just six years later, Stankonia still stands as a startling record.

It was an album both of the times and incredibly far ahead of them. There were cultural keys thrown in there that could unlock the whole world of the early millennium, yet at the same time it was all so futuristic. References rained down in a scattergun approach, while wrapped up in sounds that would come to dominate the hip-hop landscape for years to come.

In a way it was both a textbook and a how-to guide, which just about everybody in hip hop has read at least a thousand times. The fact that some are still none the wiser, as to how they did it, all these years later is a testament to its creative longevity.

Read more: Outkast’s Aquemini, the first hip-hop epic

Image: Outkast