You don’t know the real James Vincent McMorrow. But on his third LP We Move, he starts pulling back the curtain. Joined by a who’s-who of modern production – Nineteen85 (Drake, DVSN), Two Inch Punch (Sam Smith, Years & Years), and Frank Dukes (Kanye West, Rihanna) – McMorrow has crafted a release that juxtaposes disarming honesty about mental health with irresistibly sensational hooks. James Vincent McMorrow is bent on changing the perceptions people may have formed about him following his earlier releases, saying he wants to correct “people listening to my songs and believing that I’m out in the forest all day long, thinking about trees. Because I’m actually at home, trying to convince myself to go out and get milk.”

The funk-influenced Rising Water immediately signals that this album is going to be a far cry from 2014’s Post Tropical. The Nineteen85-produced track is decorated by a cheeky little digital synth that sounds like it came straight out of the 80s. McMorrow’s unmistakeable, lofty vocals are as fragile as ever, but traverse the track’s space with a newfound urgency.

I Lie Awake Every Night sounds, to put it crassly, like a 90s RnB ballad made new – and it works so damn well. On its surface it reads like a love song, but McMorrow wears his anxiety on his sleeve, being brutally honest about the way his internal struggles (notably his past battles with an eating disorder) informs his maturation: “I stare right into the dark/Thinking of ways to remind myself/That it’s all a current up here/I saw a current of fear inside”.

Cards on the table: I had to stop writing notes for basically the entirety of the next song because of the irresistible groove of Last Story. It’s deceptively simple, driven by live instrumentation and a syncopated drum beat, but when those harmonies hit it’s basically impossible to not close your eyes and just feel. There’s a sense of an inevitable crashing and burning, but Last Story retains a naive determination despite the hinting that fame might be running McMorrow ragged: “Agree we liked it better before/I started singing”.

The beguiling way the vocals on One Thousand Times are manipulated – layered, delayed, drowned in reverb – makes for a truly gripping moment on the album. Glimmering and hooky, One Thousand Times houses what is one of the best choruses of this release. It’s prime sing-along material, too: globally recognisable rueful admissions of lingering feelings cloaked in acknowledgement of the impossible reality.

Self-loathing is a tricky emotion to get right in the context of art. It can come across as navel-gazing at best, outright wankery at worst. James Vincent McMorrow nails it on Evil. Sonically, it’s the most chaotic track on We Move; an onomatopoeic soundscape for the deafening internal din that is part and parcel of struggling with identity and worth. The burning private tussle is detailed so bitingly – “This used to work for me/Now I can barely even stand/How I feel about myself” – it’s wholly uncomfortable to listen to. But it should be.

Conversely, Get Low takes the discomfort one step too far. It’s a bitter screed about hating a former partner’s newfound happiness, the lyrical cousin of Hotline Bling. The extraordinarily cheesy electric guitar motifs don’t help, either. This brief denouement into distasteful territory isn’t enough to ruin the album, though.

“Then I call you up/Convince you it’s someone else/Somebody sure/That I’m still in love/But I’m not sleeping at night/I’m afraid I could die/Without leaving a mark”. Perhaps McMorrow knows Get Low is a tad obnoxious, because Killer Whales is its quasi-apology, cloaked in self-awareness at his emotional gaffes. He’s not exactly contrite, but he’s acknowledging his foibles, wrestling with the questions of how to overcome them but coming up empty-handed.

While much of We Move seeks to address issues of mental health in the context of a failed, circular relationship, Seek Another is a true descent into the abstract absurdity that, for some, is a cerebral reality. Driven by a tense, sinister piano that eventually releases into mania via an ingenious use of a flanger, this song may not make much sense to you if you’ve never felt the whirling descent into cognitive dissonance. Either way, it’s still a wild ride.

In Surreal, McMorrow is reaching out a hand, desperate for help – or at least understanding (“Are you hopeless/Like me”). Thanks to the blissful, wide-sounding instrumentation, though, there’s a definite flicker of promise here despite that sentiment.

Closing track Lost Angles is the only song on this album that would’ve felt just as at home on Post Tropical. It’s incredibly sparse in comparison to the other nine offerings, but manages to hold your attention with a slow-burning build and the fact that McMorrow’s voice is much louder, much more clear in the mix than it previously has been. Each bluntly-put repeated assertion – from “Who am I to own you?” to “Don’t let fear control you” cuts deep, shaking the listener out of their emotional reverie. Although not as interesting as some of We Move‘s other tracks on first listen, it’s just as affecting – and manages to tie up the existential loose ends we’ve been presented with.

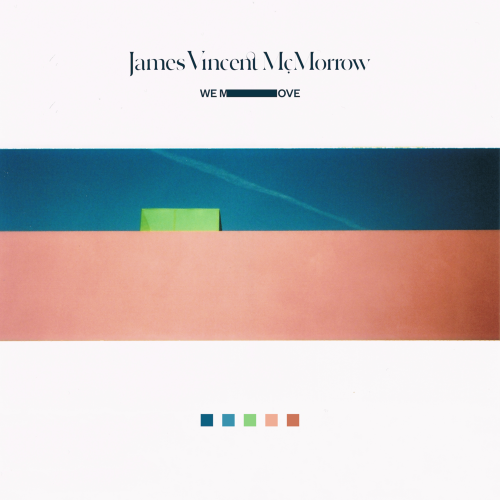

Image: JamesVMcMorrow.com

Read more: James Vincent McMorrow on wasting moments