Hangovers suck. Anyone who’s experienced one will know why, and those who haven’t will know the stories. But they’re also hard to describe, to pin down the exact reason for the horror. Headaches? Churning stomach? All of the above, but also something else. Something intangible. Maybe it’s the knowledge that this was all your own fault. A terrible feeling, to know that it was your actions alone that fucked you. And while a hangover is a relatively minor example of this, there are others. Situations that are crushingly horrible. These are the situations that Slint’s second and final album Spiderland deal with. It’s like listening to a 40-minute mental breakdown. But the beauty of Spiderland is that you never quite know if that breakdown is the band’s… or yours.

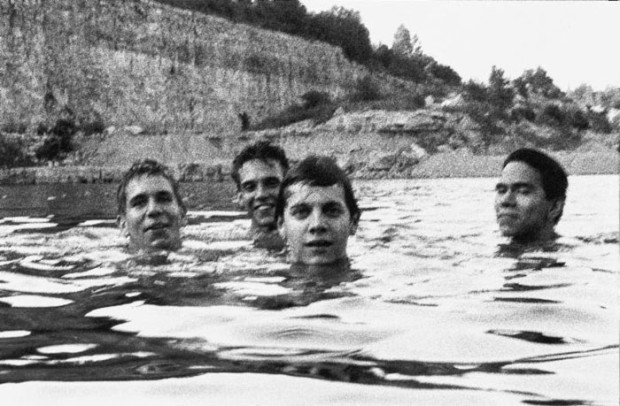

Slint is far from my favourite band, but Spiderland is my favourite album. It’s been the soundtrack to some of the weirdest and worst times in my life, which seems a weird choice. It’s not exactly a feel-good record. The recording sessions famously pushed the band well over the edge of breaking point. It’s easy to hear why. The lyricism and the instrumentation come together to make something magnificent, but also unnerving. The sounds are never particularly relaxing, but they don’t jolt you awake either. Instead, the music sits in that uneasy middle ground that burrows its way into your skull. It’s there, but rarely demanding your attention.

Spiderland is a landmark album in post-rock, but it’s a curious case. Slint’s magnum opus is not really a post-rock album. It leans more on post-punk influences, with its fickle attitude towards formality. The song structure again fits the uneasy attitude of the record, with formality present but only occasionally followed. The tracks never seem to slip into the free-flowing blank slate that comes with a complete abandonment of all musical formality. But they also never seem to follow the rules exactly. Slint push the rules to the edge, but they also hold back enough to prevent a complete collapse.

But back to it being a landmark record. How? Many people have never heard of it, so how can it be that big? Well, this was the record that effectively created post-rock. Any sad or sombre movie trailer music you heard that consists of distorted guitars and lonely strings came out of this album. The band’s guitarist David Pajo recalled a conversation he had with reviewer Steve Albini in 1991, just after the record’s release. “He said: ‘I don’t think you guys will ever get big, but you’ll be really influential. I was thinking: ‘You’re fucking crazy.'” He was right, of course. The band never really found a large deal of success. They split up in the same year they recorded Spiderland, which only went on to sell around 5,000 copies at time of release. The record’s true victory came in 1999, when Mogwai released Come On Die Young. As the Scottish post-rockers released their second album, Slint’s own sophomore album was propelled into the spotlight. Stuart Brathwaite, vocalist for Mogwai said in an interview that “[Slint] cultivated this sort of psychic playing.”

Psychic playing? What does that mean? Surely if Mogwai’s CODY sounded similar to Spiderland, why is the album such a big deal? Well, first of all, CODY and Spiderland don’t actually sound alike at all. Mogwai’s album is still distinctly Mogwai, albeit subdued and more somber. They don’t come close to Spiderland. The psychic playing Braithwaite refers to is as clear as day when you start listening to the album. From the opening chords of Breadcrumb Trails, a song which traces an unsettling day at a carnival, metaphors swirling around sex and childhood imagery, the genius is apparent. The simplicity of the first track from an instrumental standpoint betrays the complexity of the lyrics. The weird thing is that it isn’t dark, musically. The playing is heavy handed, but the notes themselves are sunny. The creepiness lies in the imagery. “Far below, a soiled man. A bucket of torn tickets at his side he watches as the children run by. And picks his teeth.”

The shift in tone, then, is startling when Nosferatu Man begins. A more traditionally structured song, the uneasiness remains. Unconfident singing from Brian McMahan lines the track, but the real power here is the guitars. The vocalist is not in control here; he is merely trying to maintain the illusion. It forms an image in the listener of a battle between the band and the singer. The guitars are darker, pronounced, and deeply forceful. It’s a confident track, but not an uplifting one.

Following this is the drum-less Don, Aman; a whispered tale of the depressed, socially anxious Don. The opening words of “Don stepped outside,” followed by the haunting strumming after will forever be in my mind. It’s a subdued and yet beautifully troubling track. A tiny glimpse of power is present, but mostly the song lingers on the mellow. In a similar vein, Washer follows it. Posing as a soft, ballad-esque song, it’s actually a suicide note in disguise. In fact, when an acquaintance of the band found the handwritten lyrics to Washer, she mistook them for just that. “Goodnight my love, remember me as you fall to sleep,” McMahan croons. The guitars don’t overwhelm, as they did on Nosferatu Man, instead opting to observe quietly the intimate conversation between lyricist and listener. Only when the conversation is over, with a resolute “I am safe from harm,” does the volume pick up, sweeping the listener away.

For Dinner… is next, and there’s not too much to say here. The only instrumental on the album, it’s about five minutes of somber playing. There’s a mixture of gothic and almost western vibes here, but not country western. No, more the type of feeling one would get from reading Blood Meridian. A darker presence, not dwelled on, just presented without ceremony.

And here we are, the final song of the album. Good Morning, Captain is one of my favourite songs, and it always has something new to offer. It times in at just under eight minutes, and blends everything up to which Spiderland has been leading. Gothic and deeply poetic lyrics drive this one forward, telling the story of a ship’s captain washed up on an icy shore. The duality of McMahan in his delivery of both the captain’s lines in a vulnerable voice and the tale as told by the narrator is remarkable. In the end, the two blur together, leading to a moving and haunting cry of “I miss you!” pouring from the speakers. This is where the record demands attention, grabbing you by the ears and screaming pained poetry at you. In terms of instrumentation, harsh distortion is the name of the game here, capturing the desperation of the lyrics. It’s frantic and heavy, and I love it. The story goes that McMahan finished recording this track and immediately ran to the bathroom to vomit, the song taking that much out of him.

And thus ends Spiderland, one of the greatest albums ever made. A record that defined a genre, but also a generation of listeners. If The Earth Is Not A Cold Dead Place is the opening to the world of post-rock, then Spiderland is the opening to the world of introspective, dark and intensely gothic art. Now, let me nurse my hangover.

Image: Bowery Boogie