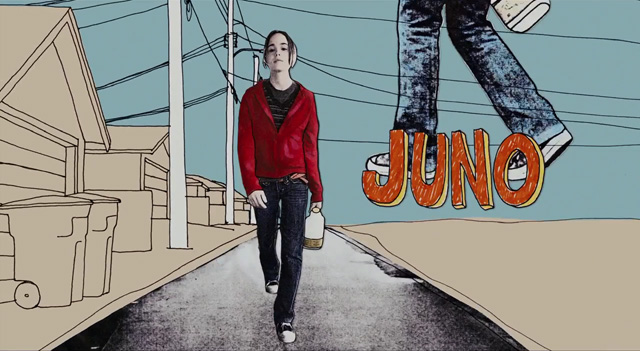

The year was 2008 and I was starting Year 11 a little later than my friends. Having spent almost four months with my family in South America, I had a lot of catching up to do. According to all my friends, the first order of business had to be watching the film they had all already seen. Juno. So I did.

Maybe because I had been removed from all the hype surrounding its release, having literally been in a one horse town, but the movie didn’t really live up to the expectations. Sure, it was witty and a bit quirky, but it didn’t seem all that real and certainly carried an air of unchecked privilege about it. It didn’t exactly present the reality of any of the people we had known who got pregnant as teenagers and I didn’t really get why my friends found it so endearing considering that fact.

One thing I did get was that it had a top-notch soundtrack, one that did a stellar job of meshing the film’s characters to the music they would listen to (and play), regardless of whether or not I actually liked them (which is to say, I did not). The film reinforced in my mind how key soundtracks are to movies, but they’re not as easy to navigate when it comes to trying to wrap your head around how certain songs end up in movies in the first place.

Over time, many films remind us how important music is as a storytelling device. From Amy and Straight Outta Compton which use the material of their subjects, to Skeleton Twins and blockbuster hit Magic Mike XXL which both had take-away scenes featuring memorable, throwback tracks in an effort to both provide comedic relief and drive character development (yes, I did reference Magic Mike, because I want it that way, pun fully intended). Soundtracks are important for myriad reasons and in some instances, they can make – or beak – a film. Putting all creative efforts aside, it takes a lot of time, effort and money to put them together and to do it legally.

When Hypnotize starts up in the middle of a party in 10 Things I Hate About You, it’s natural as can be. People are chatting away, suddenly the song starts up and we pan to the living room room where one of the primary characters is dancing on-top of the table. The reality is however, that not only was that song added in post-production as the behind the scenes footage taken during filming makes very clear, but it would have taken at least two separate licences and probably a few weeks, if not months, to get the go ahead to include it.

For starters: every song has two parts to it, and you need a licence for each. The publishing (or synchronising) rights make up the written composition and the master rights pertain to the particular sound recording a filmmaker going to use. In some instances, there may be a number of parties with publishing rights. Say you wantThe Chain by Fleetwood Mac for your movie: you need all five songwriters to give you the legal go ahead, along with their label and whoever owns the rights to the particular recording you want to use.

Typically, pulling together a soundtrack is a post-production effort. Even when a song is referenced in the screenplay, it might not always make it into the film. For instance, there may not the budget left for music when the time for music does come. Songs that play during the opening and closing credits in particular, can come at some pretty hefty prices, as they set the overall tone for the production. When there isn’t money left for music, filmmakers may look to relatively unknown artists in hopes that they will provide their songs under a gratis licences – that is, for free, but still legally contracted to the filmmaker. Or, they may find something in the Public Domain that has all the components of the composition arranged so that it does not require further licensing.

Often, a song that may have fit the screenplay doesn’t work for the actual film. In the case of the 2012 film The Perks of Being A Wallflower, David Bowie‘s Heroes replaced Fleetwood Mac‘s Landslide, which had been heavily referenced in the original book. Heroes ended up in the film because, according to writer-director Stephen Chbosky, Landslide was too soft a ballad to fit with the footage.

Though there is the risk of not getting exactly what you were hoping for back, when it works, hiring a composer to take care of all the music for a production works well. Watching Richard Ayoade’sSubmarine, there is little doubt thatAlex Turner’s soundtrack was the only one that would have worked for the film and it holds up as an album on its own. Having a Composer Agreement in place will spell out who exactly owns the film as the publisher: the film maker or the composer.

A song written into the script, however, needs to be cleared in the pre-production stages. A character singing a pop-radio track in the shower? No matter how badly they might be butchering it, it still needs to be cleared for use.

Had that song by The Moldy Peaches’ that Ellen PageandMichael Cera play together at the end ofJuno not been cleared, they might not have had a movie. What a thought...

Image: Views From The Sofa