Kendrick Lamar has been nominated for 11 Grammys, which is an incredibly impressive feat for any artist, but not one which seems to be slowing him down. He’s been chosen to induct N.W.A into The Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, gone platinum, received the key to the city of Compton, and released a number of ambitious projects.

The Grand Marshal of the annual Compton Christmas parade and several of his collaborators sat down with Grammy.com in order to shed more light on the process that went into making one of the most important albums of 2015, To Pimp a Butterfly.

Delving into the thought process that went into producing the alluringly ambiguous album title, Kendrick says that it “grasped the entire concept of the record. [I wanted to] break down the idea that being pimped in the industry, in the community, and out of all the knowledge that you thought you had known, then discovering new life and wanting to share it.”

Kendrick Lamar explains that the major influence to creating the album arose from traveling to Africa, and attempting to find a way in which to share that experience with people. Including how to describe a completely different world to those that only know one.

“I felt like I belonged in Africa. I saw all the things that I wasn’t taught. Probably one of the hardest things to do is put [together] a concept on how beautiful a place can be, and tell a person this while they’re still in the ghettos of Compton. I wanted to put that experience in the music.”

He goes on to explain where the idea for the track Complexion (A Zulu Love) originated from, and how once again his trip to Africa played a role.

“The idea was to make a record that reflected all complexions of black women. There’s a separation between the light and the dark skin because it’s just in our nature to do so, but we’re all black. This concept came from South Africa and I saw all these different colours speaking a beautiful language.”

Rapsody, a fellow Grammy nominated rapper with whom Kendrick collaborated with on Complexion (A Zulu Love), elaborates about what the ambitious rapper told her the song needed to be about, and explains that Kendrick’s initial vision for the track was rather different from the one experienced in the final product.

“He said he wanted to talk about the beauty of black people. I told him to say no more. What tripped me out is Kendrick originally said that he didn’t want to do a verse on there. He wanted me to do two verses and Prince to do the hook.”

Kendrick Lamar explains why we never ended up with Prince being one of the featured artists on To Pimp A Butterfly, stating that at the end of the day it simply came down to time management, or lack thereof.

“Prince heard the record, loved the record and the concept of the record got us to talking. We got to a point where we were just talking in the studio and the more time that passed we realized we weren’t recording anything. We just ran out of time, it’s as simple as that.”

Regardless, the finished product was amazing even without the legendary Prince. In fact, Kendrick Lamar explains that his collaborator, Rapsody, definitely brought the entire song together, allowing the track to explore themes he would be unable to probe on his own.

“Immediately when I heard the beat I heard [Rapsody’s] voice and vocal tone. But what made her special was that I knew that she was going to bring the content from a woman’s perspective about complexion, being insecure and at the same time having gratitude for your complexion.”

When talking about the incorporation of funk into the album, which had a notably different sound from what he had been using in both Section. 80 and good kid, m.A.A.d city, the rapper recalls that part of it came down to an accident and what he interpreted as a challenge while out on tour with Kanye West, while being accompanied by Flying Lotus.

“I was on tour with Kanye [West] and I had Flying Lotus with me because I wanted to work on the bus studio. He would make beats and it was one particular beat that he forgot to play. He skipped it but I heard about three seconds of it and I asked him, “What is that?” He said, “You don’t know nothing about that. That’s real funk. … You’re not going to rap on that.” It was like a dare.”

Thundercat, who is the co-producer of the album also recalls that Flying Lotus played an integral part in crafting the albums first track, “[Wesley’s Theory] started with Flying Lotus and I sitting on the couch in front of the computer analysing George Clinton.” He recalls, “he became the fuel for creating.”

Though when it came time for seeking out George Clinton for more than just inspiration, Kendrick Lamar reminisces that tracking down the architect behind P-Funk for a collaboration wasn’t that simple.

“I had to find George Clinton in the woods, man. He was somewhere in the South and I had to fly out to him. We got in the studio and just clicked. Rocking with him took my craft to another level and that pushed me to make more records like that for the album.”

When recalling some of the darker and more intense songs of the album, Derek Ali, the mixer and co-engineer talks about the session during which Kendrick Lamar was recording U, and the intensity surrounding that particular time in the booth.

“[The] session [for “U”] was very uncomfortable. [Lamar] wrote it in the booth. The mic was on and I could hear him walking back and forth and having these super angry vocals. Then he’d start recording with the lights off and it was super emotional. I never asked what got into him that day.”

Kendrick himself remembers that it was a particularly difficult period of time for him. A pivotal point in which he was feeling like he was not only evolving into a different artist, but potentially a different version of himself as an individual. Part of which was likely triggered by the recent spate of police shooting of young African-Americans.

“It was real uncomfortable because I was dealing with my own issues. I was making a transition from the lifestyle that I lived before to the one I have now. When you’re onstage rapping and all these people are cheering for you, you actually feel like you’re saving lives. But you aren’t saving lives back home. It made me question if I am in the right place spreading my voice. “Should I be back home sending this message or be on the road?” It put me in this space where I was in a little bit of a dilemma. I sat on the beat [for “The Blacker The Berry”] and then the Trayvon Martin and Mike Brown situations happened and I knew that this needed to be addressed.”

Finally the King Kunta rapper addressed the idea that he is being labelled as a “conscious rapper”. Not chuffed with the term, he instead chooses to break it down.

“If you speak on this kind of subject matter you’re labelled a conscious rapper. I don’t even know [if] that word conscious can only exist in one field of music. Everybody is conscious. That’s a gift from God to put it in my heart to continue to talk about this because that’s how I’m feeling at the moment. The message is bigger than the artist.”

Kendrick Lamar finishes the interview, by elaborating on an example in which he believes the message was bigger than the artist that was attempting to communicate it, and how occasionally that message can outlive the artist and manifest itself within others.

“When Tupac was here and I saw him as a 9-year-old, I think that was the birth of what I’m doing today. From the moment that he passed I knew the things he was saying would eventually be carried on through someone else. But I was too young to know that I would be the one doing it.”

Feel free to check out the full length interview, here.

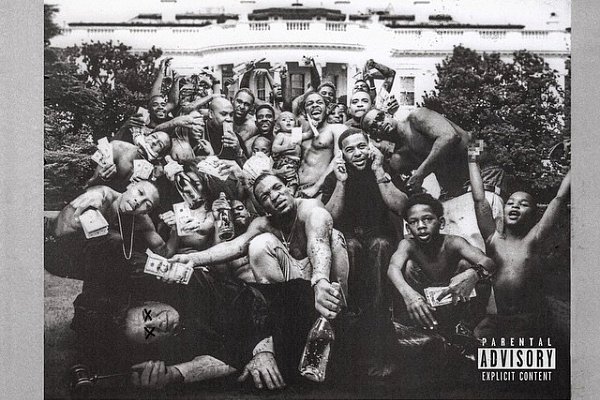

Main Image: Rolling Stone