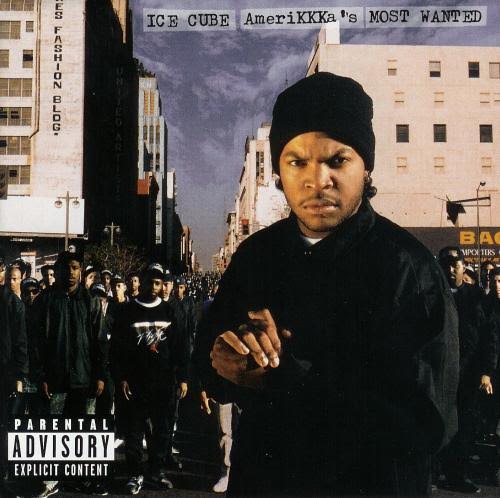

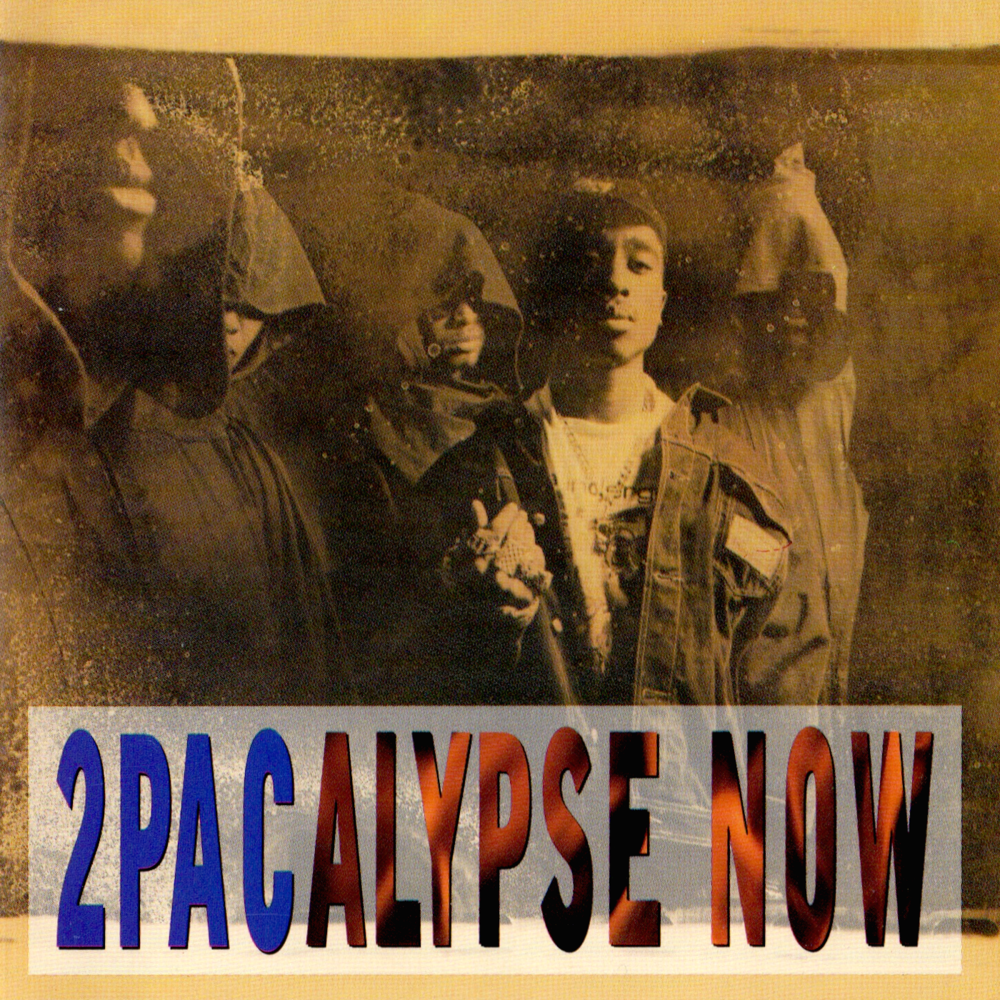

In 1990, Ice Cube released his debut studio album provocatively titled AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted. A year later, the relatively unknown 2Pac would also release his debut album, 2Pacalypse Now.

At the time of its release, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted was running off the breakout success of lyrical writer and rapper Ice Cube, a key member of N.W.A., whose 1988 album Straight Outta Compton arguably brought gangster rap into the disapproving gaze of mainstream music. After his almost immediate departure from the group due to some financial disagreements, Ice Cube began working on his debut album, with the hip-hop world patiently waiting to hear what this artistic prodigy had to offer as a solo artist.

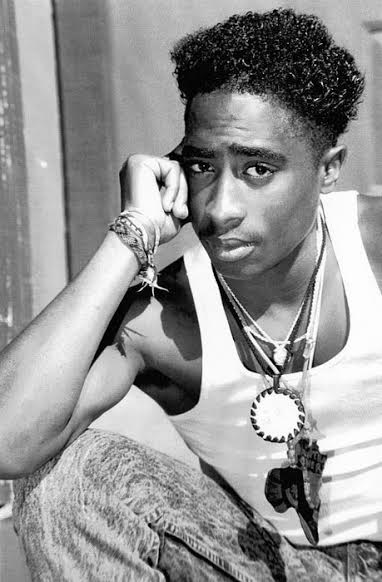

Alternatively, after attaining a level of exposure as a member of Digital Underground, 2Pac first showed off his rapping skills on Same Song before going on to feature on the album, Sons of the P – a second album for Digital Underground. His solo debut album was released to a general public largely unaware of his existence.

Today, both artists are considered to be pivotal to any discussion regarding hip-hop, and have both become household names. Both artists, interestingly, found fame at an early age. By the time of his first solo studio album release, Ice Cube was only 21 years old, achieving fame two years earlier with his previously mentioned involvement with N.W.A. Comparatively, 2Pac was 20 when his solo album dropped, still relatively unknown. Arguably, both albums were pivotal in shaping these two artists and their youth was a relevant factor. These albums introduced the world to two distinct individuals and set the benchmark for the type of music that could be expected from each.

To listen through each album, it’s evident that both artists share a deep-seated hatred and mistrust of white America’s dealings and attitudes towards the African-American community, specifically regarding their treatment of young black men. These attitudes, although only briefly touched upon in AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, are clearly one of the defining forces behind the raw and angry vocals of Ice Cube throughout, and are also somewhat obviously laid out in the album’s title. The first and second tracks of his debut album immediately set the scene for what will follow: both songs deal with issues of race and prejudice but do so in a way that allows Ice Cube to come across as an intimidating individual, he’s telling you that’s what’s up and daring you to challenge him on it.

Ice Cube presents himself as a ‘gangster’ – why this? Probably because of their affiliation with the Mafia – it’s an appropriated term implying strength, power, and a willingness and propensity to violence and murder. Not least, gangsters are involved in illegal activity. The mere action of calling oneself a gangster – in a social situation where Black men are commonly thought of as being criminal – is a way of taking that stereotype and turning it into a signifier of strength: fear me, because I can and will fuck you up. What’s more, you deserve it for all of the shit you have put me and my people through.

In the album’s titular track, Ice Cube points out the double standards of the police’s attitude towards young black men:

I think back when I was robbin’ my own kind,

The police didn’t pay it no mind,

But when I start robbin’ the white folks,

Now I’m in the pen wit’ the soap-on-a-rope.

On the track Turn Off the Radio, Ice Cube doubles down on his message of double standards when he rhymes about his tracks not receiving radio play. He addresses what he deems the problematic trend of African-Americans attempting to whitewash themselves so as to appear more gentrified to white consumers, labelling them an “Oreo cookie”. Next he expresses his disdain towards radio stations:

Personally I’m sick of the ass-kissing,

What I’m kicking to you won’t get rotation,

Nowhere in the nation,

Program directors and DJs ignored me,

’Cause I simply said, ‘Fuck Top Forty!’

It’s perhaps not surprising that Ice Cube’s debut album was mostly ignored by mainstream radio, since the content was in stark contrast to what charted in 1990.

The theme of double standards appears again on the track Endangered Species (Tales from the Darkside). There, Ice Cube calls out law enforcement attitudes towards the black community, saying that even if he wanted to stop being a gangster, it wouldn’t change the way a police officer would see him – and that’s precisely because he is a young black man:

That I can say peace and the gunshots will cease?!,

Every cop killer goes ignored,

They just send another n*gga to the morgue!

A point scored, they could give a fuck about us,

They rather catch us with guns and white powder!

If I was old, they’d probably be a friend of me,

Since I’m young, they consider me the enemy!

The idea that young black men born into an impoverished and shunned environment can only be expected to head in a negative direction is felt most on the track Once Upon a Time in the Projects. Ice Cube tells a story to a child, using well-known story-book figures depicted as common tropes of a ghetto lifestyle, to showcase that the standard telling of these stories would not be easily relatable to black children raised poor. So “Ice Cube’ll tell the kids how the story should go…”

Finally, the theme of showcasing the common situations that arise in the ghetto are made clear in the track Who’s the Mack?. Here, Ice Cube points out the common manipulators and opportunists he and others encounter in their day-to-day dealings in the projects, and asks the question: who is really being manipulated, and by whom? The implication being that, regardless of what you think, the real manipulators are the ones who put you into the ghetto.

It’s important to note that although the album attempts to highlight the ways in which one can rise up from the struggles of being a young black man growing up in the ghetto, Ice Cube has almost nothing positive to say about women born into the same circumstances. In fact, with the exception of one song, not ironically titled It’s a Man’s World, Ice Cube’s attitudes can only be expressed as wholeheartedly misogynistic.

It would be easy to excuse Ice Cube’s attitudes towards women as a simple product of what was expected of a young black gangster rapper at the time. In fact, tracks such as, I’m Only Out for One Thang and Get Off My Dick and Tell Yo Bitch to Come Here are just that: empty boasting about just how much sexing Ice Cube does and how he manages to do all that sex without building any emotional ties. However, the song You Can’t Fade Me, in which Ice Cube deals with a young woman telling him that he is possibly the father of her child, elicits incredibly violent thoughts and potential courses of action.

Initially, Ice Cube thinks that the best response would be to simply kick the woman in the stomach to terminate her pregnancy, but then thinks better of it:

What I need to do is kick the bitch in the tummy,

Naw, ’cause then I’d really get faded,

That’s murder-one cause it was premeditated.

He chooses, instead, to see how this all pans out, but hopes that she isn’t lying to him:

But if I find out your tryin’ to fake me,

I’m a buff that duff and hoot,

Beat ya down and leave a crown or two.

Luckily (for everyone involved), Ice Cube gets a blood test after the child is born, and it turns out he isn’t the father after all. Generously, he allows the woman in question to live, even though she caused him several months of stress and ridicule from his peers who thought the whole thing was hilarious. He has second thoughts about it, though:

“Damn, why did I let her live?

After that I should’ve got the gat,

And bust and rushed and illed and peeled the cap.

It’s notable that this is by far the most misogynistic song on the album, and Ice Cube – not one to alienate his potential female audience – somewhat makes amends for it in the track, It’s a Man’s World. In this song Ice Cube and Yo-Yo, a relative unknown female artist, trade gendered barbs in regards to women’s and men’s places in the rap game. In the end, they both attain a mutual respect for one another, however the overall theme can be summed up with the ending of each verse:

[Ice Cube]

This is a man’s world, thank you very much.

[Yo-Yo]

But it wouldn’t be a damn thing without a woman’s touch.

It’s disappointing that although Ice Cube’s album attempts to gather some sort of positive outlook for young black men, it completely disregards young black women, who presumably would be facing incredibly similar hardships and prejudices as their male counterparts, while also suffering by receiving little to no support from the men in their community. This is just one of the negative themes that can be attributed to the album AmericaKKKa’s Most Wanted – one which kicked off the lucrative and timeless career of one of hip-hop’s greatest rappers.

Comparatively, 2Pac’s 2Pacalypse Now employs a political rather than gangster tone regarding the struggles faced by young black men. The tracks focus on police brutality and a call to unify the black community to rise above (what he perceives to be) a reality constructed by white America to keep them oppressed and unable to fulfill their potential.

On the introductory track, Young Black Male, 2Pac specifically distances himself, as an individual, from the drug game, rapping faster than what would come to be expected from him in his later albums:

I’m packing a gat cause guys wanna jack,

And fuck going to jail,

’Cause I ain’t a crook, despite how I look,

I don’t sell yayo,

They judging a brother like covers on books.

It’s an interesting approach; 2Pac acknowledges that he was mixed up in the drug game in the past, but he rarely boasts about a present involvement with drugs and robberies – themes which are typical of gangster rap. Instead, he focuses on being an artist, and shinning a light on the struggles of an average young black man, not one pursuing a criminal path.

The theme of police brutality, often directed at young black men for the crime of simply being a young black man, is a predominant one, focusing on the feelings of despair and helplessness of those caught in the system of racial profiling. To elicit some kind of understanding 2Pac attempts – in the track Trapped – to get the listener to connect with him as a young black man constantly profiled by law enforcement, waiting for the day that he slips up and commits any type of offence:

They got me trapped,

Can barely walk the city streets.

Without a cop harassing me, searching me,

Then asking my identity.

The attitudes conveyed towards young black men by the police as “guilty, until proven innocent”, are also explored on the track Violent, where the protagonist is pulled over by police and asked to step out of the vehicle. He chooses to cooperate and is rewarded with a roughing up and an attempted framing:

They tried to frame me,

They tried to say I had some dope in the back seat,

But I’m a rap fiend, not a crack fiend.

The song’s title is in itself a commentary on the attitudes that young black men experience by figures of authority, particularly those who are white Americans. 2Pac rationalises that since that’s their attitude, it’s perhaps not surprising that illegal activity is exactly the direction a lot of young black men choose to take – a self-fulfilling prophecy:

You wanna sweat me, never get me to be silent,

Givin’ them a reason, to claim that I’m violent.

Indeed, the same theme of being forced into a lifestyle because of a predominantly racist attitude and lack of help from the rest of the society is also explored in Soulja’s Story with an intro stating:

They cuttin’ off welfare,

They think crime is rising now,

You got whites killing blacks,

Cops killing blacks, and blacks killing blacks,

Shit just gon’ get worse,

They just gon’ become souljas,

Straight souljas.

The song goes on to show a glimpse of a vicious cycle through a fictional story in which a young black man chooses the criminal lifestyle of being a drug dealer and gets caught, only to have his little brother follow in his footsteps. While attempting to break his older brother out of prison, both are shot by police.

The difference between these stories when compared to other artists dealing with similar themes is the easily relatable narrative and realism that 2Pac brings with his storytelling. It’s not entirely difficult to imagine that these exact situation played out in real life, with the same very real consequences taking place.

2Pac’s gloomy outlook on racial prejudice wasn’t just limited to law enforcement. The track I Don’t Give a Fuck sheds light on everyday racism, and racism in the music industry:

The cabs, they don’t wanna stop for a brother, man,

But damn near have an accident to pick up another man,

I went to the bank to cash my check,

I get more respect from the motherfucking dope man,

The Grammys and American Music shows,

They pimp us like hoes, take our dough, but they hate us though.

The overwhelming hopelessness of being treated as a second-class citizen, and a call to rise up against it is not felt anywhere more strongly on this album than on the track Words of Wisdom. Its intro, outro, two verses and an interlude serve as a dictation of all the things wrong with white America’s attitudes towards not only young black men, but the black community as a whole. 2Pac points out numerous issues, but instead of trying to rouse a violent response, he calls for the black community to rise above it all through becoming more educated and proud to be black.

But it’s important to point out that not every track on 2Pacalypse Now is a revolutionary political ballad. Songs such as Something Wicked, Crooked Ass Nigga and Tha’ Lunatic are all boastful songs that are delivered in a similar style to those found on AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted.

It’s also notable when comparing the two albums that, like Ice Cube, 2Pac dedicates some time to the subject of young black women. 2Pac has two songs dedicated to this subject, but thematically they couldn’t be further from Ice Cube.

In the track most commonly associated with 2Pacalypse Now, Brenda’s Got a Baby, 2Pac highlights the issues of neglect and mistreatment that plague a young black woman growing up in the ghetto. The song, which most readers have undoubtedly heard, doesn’t have a hook and instead opts to be a no-interruption narrative. It deals with a 12-year-old girl, Brenda, who finds herself pregnant by incest to her cousin, with nobody close to her giving a single fuck. In just under four minutes it tackles the issues of rape, incest, welfare and neglect, young motherhood, prostitution, and murder. It’s a raw, believable glimpse of what it’s like for a young black woman to find oneself without any sort of support in the community, and the consequences that come with that, not just for her, but the community as a whole.

The similar issue of pregnancy and overall struggles of a young black woman are highlighted in the final song on the album, Part Time Mutha. The first verse rhymes about being raised by a mother addicted to heroin from the perspective of her son. It brings to light the issues of hunger and poverty that come from having your caretaker addicted to drugs, and the consequences of being raised in that environment as a young black man:

All those days, had me fiendin’ for a hot meal

Now I’m a crook, I steal, I do not feel.

The second verse, rapped by the female artist Angelique, touches on the subject of this woman being sexually abused by her stepfather, becoming pregnant and subsequently being cast out by her mother after telling her about it. The third and last verse is told from a perspective of a young black man who finds himself looking after a child and being unable to cope with the responsibility, expressing how difficult his life is now that the tables have turned:

So, I do the dishes and clean the floor,

When I sleep I can’t dream no more,

Oh no, now I’m a part-time mutha,

And I change the diapers and clean the shit,

The tables are turned I can’t take this.

In stark contrast to the ways that young black women are depicted on AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, 2Pac is significantly more sympathetic to the struggles that young black women face, even though they are depicted as different to his own. The sense of poverty and mistreatment by the system remains, but he also highlights the gender struggles that are unique to her situation in comparison to a man’s.

Looking back on these two albums, it’s an interesting glimpse into the attitudes and treatment that seemed to dominate the way society perceived the black community then, and how these artists themselves thought the black community was perceived in the early ’90s. Both albums are indeed a reflection of these interconnected themes, yet are noticeably different. Ice Cube chose to use his album to glorify gangster culture in an attempt to showcase the pitfalls and dangers of alienating the black community. 2Pac, instead, attempted to bring the listener into the day-to-day life struggles that came with being a part of this demographic. Both artists, in their own unique way, attempted to unify the black community and draw out the prejudices that marginalised them.

It’s easy to see why people would be drawn to the gangster style found in Ice Cube’s lyrics. Identifying with the motif of a gangster – for all its connotations – has the capacity to make the powerless feel just a little more powerful (in a typically masculine way). It’s the embodiment of an identity that will stand to violence and isn’t afraid to take you down. Nonetheless, 2Pac shows us the reality of what life is like, and that’s important too. The irony is that 2Pac is heralded as a gangster rapper – and indeed, it is possible to take these themes from his music (Thug Life!) – but where 2Pac is at his most powerful is in his invitation for you to share in the pain and desperation of cycles of systemic oppression. Such a tactic is risky; it is certainly more appealing to identify with the bravado he displays at times. But it is through the recognition of his reality, through feeling the genuine despair of a community whose liberation seems a pipe dream, that the passion and drive for change and a sense of hope can emerge. That is why 2Pac’s music is so politically powerful.

Perhaps what’s saddest of all is that the two albums, released at the start of the ’90s, almost 25 years ago, ring as true now as they did then, both in terms of the general treatment of young black men and women, and in the gender dynamics between men and women. It seems that now is a good a time as any to listen to these albums, understand the messages that the artist are trying to share, and implement the changes that are needed, regarding not only attitudes towards the African-American community, but our attitudes towards each other as a society.