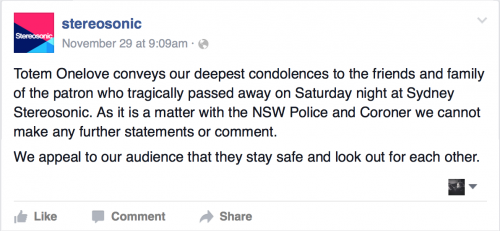

In the wake of yet another tragic death at an Australian music festival, the media and the Internet in general has pounced on the issue. With three drug-related deaths in as many months taking place at festivals, all evidence points towards a growing problem. And by evidence I mean statistics and facts, not repeated, misinterpreted, mishandled incidents. As with any problem, determining the cause is the real key.

With calls for changes in policy, policing and attitudes, there is a danger of online reporting becoming a case of bandwagon jumping and pitchfork waving as each new story details how this problem should be addressed. But one clear message rises to the fore of this discussion, and that is that whatever we are doing, isn’t working. The current official stance towards drug taking is one of zero tolerance, yet drug use has not decreased even slightly; rather, injuries and fatalities have grown.

Is zero tolerance the right approach?

To simply keep reiterating that “drugs are bad, don’t use them” is to ignore the reality. The reality is that while there may be evidence that drugs have risks and negative effects, people are still doing them. In a recent conversation I took part in, someone compared drugs use to driving – which is more sensible that it sounds. Cars are equipped with seat belts, airbags, you are required to be tested on your knowledge and understanding before you are allowed to use one. Clearly we acknowledge that driving is a risk, due to circumstances outside of our control and often relating to an individual. So we provide the tools to help make it that much safer.

To declare a stance of zero tolerance is pretty much the same as an admission of risk. And if the reality is that regardless of this risk, people are still using, why do we not provide those same tools to minimise risk? Even as far back as 1999, police were talking up the importance of further education and harm minimisation around drug use, as well as crack downs on supply.

We accept that a heroin addict may not be able to quit, so we provide them with methadone. It’s not the ideal, but it is looking at a situation with honesty and clarity and offering up the best realistic solution at that time to help. With the irrefutable evidence to say that drugs are used at festivals despite illegality, how do we manage these situations to minimise risk? What measures if any are in place to combat what is a regrettable but real problem?

Firstly, let’s look at the festival organisers. Caught between a rock and a hard place, to offer up guidelines on drug use would be to openly acknowledge (what everyone already knows) that drugs will be used at the event. Local councils and police would be calling for immediate cancellation, prevention is the best cure after all. This leaves the option of highlighting the legal implications of drug use on the festival site, a disclaimer to simply inform patrons and absolve responsibility. So next up would be the police force, allocated to any large event. And their role is uphold the law, which as it is is one of zero tolerance, and so they are looking at supply reduction. Simply taking the measures prescribed to prevent drugs being present at the event.

What can police do to me (legally)?

Current police measures at music festivals include uniformed officers, undercover officers and drug dogs, with some larger events drawing riot squads. Drug dogs are one of the most prominent, formidable not to mention expensive measures, stationed with their handlers often at the entrance as well as moving around the site. Looking at statements from those stopped by police on suspicion of possession of drugs at a festival, the majority comment that they wish they had known their rights in this situation, or even the legal policies on drug possession. In itself this is clear indication of how restricted the discussion has become.

Legally, police have the right to stop and search any individual without warrant if they suspect they are in possession of illicit drugs. The basis simply needs to be reasonable suspicion on the part of the officer that the individual in question has illegal substances on their person. Police guidelines include factors such as time, location, behaviour and any antecedents (previous criminal record). Simply being present at a festival is not enough, but you could only contest this if the police officer used force to carry out the search. And as long as they found nothing on you.

There are also guidelines in place as to how the search must be conducted. These include reasonable privacy and employing the least invasive method applicable to the situation, and that the officer conducting a search must be of the same gender as the suspect. They also cannot question you while you are being searched; all questioning should occur before, or on finding an illegal substance. This applies to strip searches, which must also establish reasonable grounds before being conducted.

It is worth noting that if you are simply stopped and searched, you are not required to give your name unless you are under 18 or those suspicions are proved correct. However, most resources would encourage you to do so anyway, and to generally be co-operative as (to put it bluntly) it seems that you may not be immune to a police officer’s power trip if you show a little attitude. You are entitled to request the officers name, station and rank.

Of course, sniffer dogs account for a large proportion of stop and searches at festivals. As long a sniffer dog indicates that it can smell an illegal drug, which specifically includes sitting down next to you, that counts as reasonable suspicion and cause for a search. Anywhere that police are entitled to perform their duties, they are permitted to bring drug sniffer dogs. The efficacy of sniffer dogs is highly contended regarding false positives and accuracy, but this is almost never debated (or even acknowledged) publicly by the government or the police.

Where can I get information within a festival?

Third party organisations like the Red Cross are an excellent resource at events, brought in as a means of harm reduction. The save-a-mate program is specific to festivals, with information based staying safe around alcohol and drug use, and offering a helpline for those in distress. Trained volunteers move around festival sites with the aim of keeping the conversation around drug use as open and informal as possible, also looking out for those who might be in distress from alcohol or other drugs. Particular emphasis is placed on the the service remaining non-judgemental; if patrons are intimidated by a police presence, it is important for them to know that if they do run into trouble, that they can seek help without the fear of getting into trouble.

Part of this is the “chill out space” provided by the Red Cross program, a quiet area where anyone suffering from physical or emotional distress can receive aid free of judgment. Volunteers provide support, water, sick bags and advice, at the same time relieving First Aid services of more minor cases so that they are free to attend to emergencies and serious problems. Organisations like the Red Cross form the third point of this triangulated approach to tackling drugs at festivals, operating along side the police and First Aid. With an approach that ensures a proper understanding of drug use, it’s clear that when it comes to minimising the harm from these substances, education is deemed to be key.

What about drug testing?

In a similar vein, calls for greater availability of drugs testing kits are rising in the wake of recent tragedies – something which was available in Australia just a few years ago, though no longer so widespread. Allowing people to test the contents of their drugs is something that is readily available in Europe and has been for 25 years, indicating when a drug has been cut with another substance. The horror stories of rat poison, bleach and battery acid are worrying enough, however more innocuous but unknown additions could prove dangerous to specific individuals if they cause an allergic reaction. Drugs testing kits also help to ensure responsible using by confirming the purity of a substance. If users know exactly how potent something is, then the likelihood of overconsumption decreases, especially if they do not feel the effects that they looked for within an expected timeframe.

It is fair to say that once under the influence, an individual’s ability to make decisions is often impaired. So to return to the idea that prevention is more effective that medication, whilst programmes like the Red Cross are invaluable for the support they offer to people in distress, festival goers also need the opportunity to receive the educational messaging before they reach a state where they require help. In order to truly work towards preventing drug-related harm at events, the conversation needs to turn to health – not the law.