“The only place for women in music is backstage on their knees.”

I believe that was my very first encounter with overt sexism. Oddly enough, until that moment I thought I had found my place and it was most certainly in music.

I should clarify that it was a second-hand encounter. It was something said to me in a training room, not by a man, but by a woman. A young woman; a friend and mentor who was recounting her own story. A young, successful event organiser and music photographer, this was something she was told by male musician who was, at the time, fairly prominent in certain circles in Australian music.

This man was especially influential over his audience, which mainly consisted of young people disillusioned with popular music and looking for their niche. When we met a few years later, his attitude was much the same. He was active in rejecting women as fans of music or indeed professionals (musicians or industry), while reinforcing the notion that women are objects; incapable, untalented and unintelligent.

Unfortunately for many women who are involved in music: be it as musicians, industry professionals or even as fans, it’s an attitude that is not unfamiliar. Most will be able to tell you of their own experiences with the misogynistic attitudes rampant in music. From the very real threat of physical, often sexual, violence directed at women*, to the attitude that women need to prove their right to participate in music there are so many barriers preventing women from participating freely and equally in music.

“Women are called upon every day to prove our right to participate in music on the basis of our authenticity — or perceived lack thereof.” – Meredith Graves.

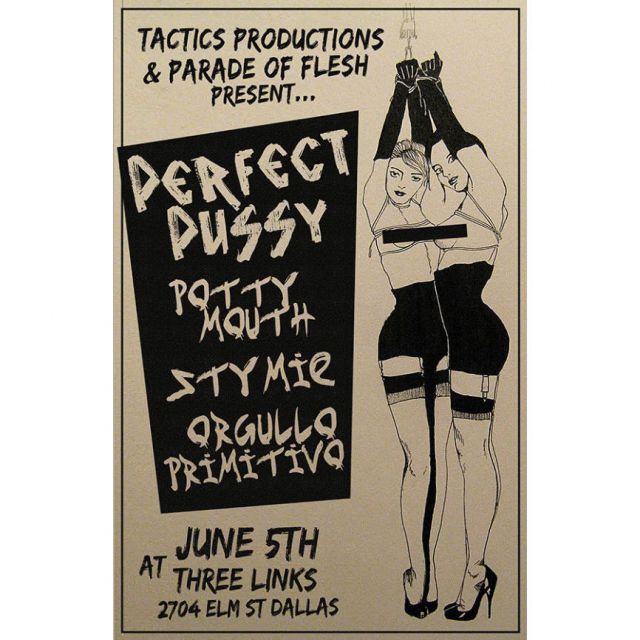

Last year, Meredith Graves, the vocalist for Syracuse hardcore band Perfect Pussy, commented on the sexism faced by women in music following a set the band cut short at three songs due to artwork on the promotional flier for their show by the event organisers.

You say you like a band you’ve only heard a couple of times?”Prepare to answer which guitarist played on a specific record and what year he left the band… This happens so often that it feels like dudes meet in secret to work on a regimented series of tests they can use to determine whether or not we deserve to be here.” These sentiments are echoed in an article written for the New Yorker by Anwen Crawford. In her piece The World Needs More Female Rock Critics, Crawford recounts a time as a teenager when she was told by a classmate that she probably didn’t even know who Bjork was – the same Bjork whose face was plastered on her binder. The same Bjork who has also spoken about the struggles of being female in the music industry, no less.

“The record store, the guitar shop, and now social media: when it comes to popular music, these places become stages for the display of male prowess. Female expertise, when it appears, is repeatedly dismissed as fraudulent. Every woman who has ever ventured an opinion on popular music could give you some variation (or a hundred) on my school corridor run-in, and becoming a recognised “expert” (a musician, a critic) will not save you from accusations of fakery.” – Anwen Crawford.

Earlier this week, we posted a feature about multi-talented Canadian artist Grimes, as well as Sydney artist Montaigne and Chrvches‘ Lauren Mayberry. Grimes spoke about the sexism she endures from all angles simply for being a female musician, with her skills as a producer being ignored all together due to her being a woman. A seasoned producer as well as songwriter, visual artist and director, she spoke about being in studios with engineers who wouldn’t let her touch the equipment. “I was like, ‘Well, can I just edit my vocals?’ And they’d be like ‘No, just tell us what to do, and we’ll do it.’ And then a male producer would come in, and he’d be allowed to do it. It was so sexist. I was, like, aghast. It made me really disillusioned with the music industry. It made me realise what I was doing is important.”

It’s a common occurrence and one I am personally familiar with. No, I am not an engineer, but I have known how to set up a PA for basic use from the ripe old age of twelve. Yet, I have found myself time and time again prohibited from touching it or have had its functions explained to me in incredibly dumbed down terms at my own shows. All the while, my male counterparts have always been free to do what they wished with the equipment. The women I know who are sound engineers often have their capabilities questioned despite having years of experience under their belt.

Other tests of a woman’s credibility in music described by Graves included stopping female musicians when they’re bumping in and asking whether they’re the girlfriend of a band member, presuming that they are not a musician themselves. In a think piece for Noisey, Emma Garland spoke of this tradition music has of keeping women at arm’s length. She too, observed that often times, women are “confined to the sides of stages playing the role of the ‘groupie’ and never the guitarist – even when they are literally the guitarist.” The concept of the groupie doesn’t stop at female musicians, either. As mentioned in Crawford’s article, in a 2002 biography of Lillian Roxon, Roxon’s young protégé, Kathy Miller, recalls being challenged by a male editor who assigned her to write about The Who and then asked for a blow job in return, saying, “What’s the big deal? You’re a groupie.” She replied, “I’m a woman who writes about rock and roll.” His answer: “Same difference.”

Even well-renowned and critically acclaimed female musicians it would appear, struggle with the concept of female presence in music. In what was probably well-meaning commentary but actually considerably harmful for the cause, Stevie Nicks spoke about the need for more women to be involved in music earlier this year. The Fleetwood Mac singer stated that every band should have a woman in it. She is one in a band of two, but I digress. Her argument for the inclusion of women boiled down to the romantic and bewitching qualities women bring to music. While I agreed with the sentiment that women should feel more supported and encouraged as musicians, the comments made on the eve of the band’s reunion tour left a bad taste in my mouth.

Nicks’ comments hark back to the idea of the role of a woman in music is to be a romantic, sexual object and not much else. An idea that is perhaps no more greatly reinforced than when it comes to music videos. Commenting on her own background as a dancer in music videos, English singer FKA twigs discussed the role of female dancers in music videos while she was promoting her own video for Glass & Patron: “I trained as a dancer from when I was eight years old and did classical and ballet and tap… And I worked my arse off when I was a kid to be trained properly and then the first music video I did it’s kind of … ‘can you put on these shorts, can you stand over here and look cute, can you rub up this rapper’s leg’?…I remember thinking, ’10 years of training … for this?’…. so when I work with dancers I try to make them feel very cared about.” She went on to express frustration at the fact that dancers in music videos are not considered athletes despite the intense physical training they endure, but they’re also not included as artists either. It is to that end then that she wanted to use her latest video to show how the dancers moved and “have it about them as much as it was about me.”

The objectification of women in music certainly doesn’t begin and end with the music video. In her interview with The FADER, Grimes went on to comment that she is constantly on the receiving end of threats of physical, sexual violence. “People want to, like, rape and kill you. It’s, like, part of the job. One time I was backstage at a show, and there was this random guy in my dressing room, and he just grabbed me and started making out with me, and I was like, Ah!, and pushed him off. Then he went, ‘Ha! I kiss-raped you’ and left. Shit like that happens quasi-frequently.”

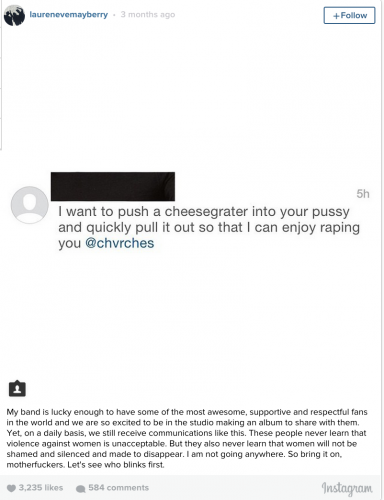

In 2013, CHVURCHES singer Lauren Mayberry, penned an article for The Guardian in which she described her own similar experiences as a female member of an incredibly successful band. Since writing the article, it would seem that she still receives sexually violent and misogynistic comments and messages on social media, including the one below, which she shared on Instagram.

In her article, the singer asked whether the “the casual objectification of women so commonplace that we should all just suck it up, roll over and accept defeat?” Indeed, that is often what we’re told to do. We are also told we are too overbearing or oversensitive when in reality, it’s a justified reaction to harassment.

A lot of this language –that which is used to pigeonhole women as being overly sensitive– is the same language that women in other industries also find themselves coming up against. Female band managers, like female CEOs, are bossy. Female event organisers are control freaks. Female critics are just bitches who don’t know anything about what and actually just want to jump on every male musician’s dick. Case in point: at a show earlier this year, Sun Kil Moon singer Mark Kozelek had this to say (and then sing) about music journalist Laura Snapes:

“There’s this girl named Laura Snapes, she’s a journalist. She’s out to do a story on me, has been contacting a lot of people that know me… Laura Snapes totally wants to fuck me / get in line, bitch…Laura Snapes totally wants to have my babies.”

For a community often so proud of being accepting and open minded, music is in fact pretty closed off to women. We live in a world where songs like Robin Thicke’s Blurred Lines can reach Number One in fourteen countries before people being to question its content while Taylor Swift is vilified for writing songs about her love life – and age old aspect of songwriting. Female musicians and fans alike turn up at shows unsure of whether they’ll leave the venue safely. Women fight to prove our worth as fans and professionals working in the industry despite having the same (or in some instances, more) credentials to their names than their male counter parts. We’re described as “bossy” and “bitches” for doing our damn jobs and told that we’re being too sensitive to something that’s always been the way of this world. Well, honestly, that’s just a bit of bullshit.

In Victoria, there are some movements toward change. The Victorian Government has been working with lobby group LISTEN to put together a taskforce to help make live music venues safer places for women. The call to the music industry to take ownership of the problem and work towards a solution follows numerous incidents of sexual harassment and physical violence, including one where a woman was ejaculated upon at St Kilda Festival earlier this year. It is hoped that as a result of the taskforce, venue operators and security staff will be better able to respond to sexual harassment within venues. In the meantime, supporting female musicians, pushing to diversify lineups for festivals and gigs alike and changing the language used to speak about women in music are steps we can take as individuals.

Perhaps the man I quoted at the beginning of this article had his comments taken out of context. Perhaps that statement was actually his grant social commentary about the space that is so lacking for women to feel safe and encouraged and empowered in music. While I highly doubt that is the case, I do know this: that quote has done more to galvanise me than any other singular experience in music and I hope it does the same for someone else.

* I don’t speak for them, but I include trans/non-binary women.