Being that I have a love for most things hip hop

Not you Chris Brown, the loyalty of these hoes aside.

I am more than aware of the power that guest verses can have on the entire game. In hip hop’s earliest beginnings, before the arrival of the Internet and social media with the ease with which anyone can self-record and release their music and boost anyone’s status from nobody to celebrity, the only surefire way to break if you were an upcoming artist was to be good enough that a record company would offer you a deal and pay you to record your music for distribution.

In order to get backed by a record label though, you usually had to get heard and have some kind of fanbase. Underground radio and the tape trading scene were two ways to spread your reputation, but hip hop history is littered with examples of some of the most notable artists getting their big break by guest versing on the songs of already established stars.

The Notorious B.I.G. did his first work as a guest on Heavy D and the Boyz A Buncha Niggas, as well as appearing on remixes by Mary J. Blige and Craig Mack, for which he rode the acclaim all the way to a debut LP in Ready To Die. Tupac was a roadie and a back up dancer for hip hop crew Digital Underground before being allowed a verse on Same Song and everyone realised he was even more talented than the crew he was carrying shit around for. Everyone knows Snoop got his big break on Dr. Dre’s The Chronic, Eminem received similar treatment on 2001.

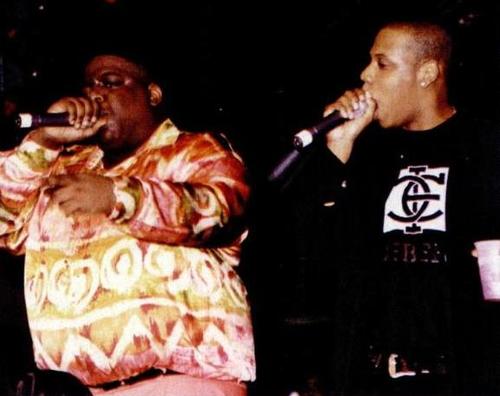

The reverse was also commonplace, with already established artists guesting on album tracks by up and comers. My absolute favourite example of this was Biggie teaming up with a young Sean ‘Jay-Z’ Carter on the latter’s Reasonable Doubt. If you haven’t heard Brooklyn’s Finest off of that album then you have some kind of unnatural aversion to all things good.

The reasoning behind it all was simple. It provided an avenue for previously unheard of artists to receive maximum exposure. They gained immediate credibility by association and, once established, guest features between those same artists became a highly successful cross-marketing strategy, tapping into multiple fanbases at a time. That the music being created in these glory days was so wonderfully transcendent was the diamond-encrusted cherry on top. Seriously, look at some of the collaborations we’ve enjoyed:

The Notorious B.I.G. and Junior M.A.F.I.A. (the group headed by Lil Kim) on Get Money and Player’s Anthem. A severely pissed off Ice Cube and the immortal Chuck D on Endangered Species (Tales From The Darkside). Pac and Snoop’s juxtaposing fire and syrup flows on 2 Of Amerikaz Most Wanted. Possibly the most terrifyingly violent super team up between rap crews Onyx and Wu Tang Clan on The Worst. Warren G and Nate Dogg on the superbly smooth Regulate. Dre and Eminem grabbing rap by the throat in Forgot About Dre. DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince!

I could go on all dang day, these are just some of my favourites. There is no denying then that some of the greatest and most successful rap songs of all time have been the result of collaborations. You would think with such a simple and successful model for success that the rap game in the 21st century couldn’t possibly have fucked it up, right?

We’ve gone from artists teaming up being good for both business and music, to an all-out incestuous circle jerk amongst labelmates. We’ve gone from artfully constructed albums with a healthy variety of guest features that make sense to slapped together singles featuring three or four artists rapping about expensive things or gangsta things or expensive gangsta things with little to no connection whatsoever. There’s absolutely no sense of the camaraderie or community like there was in the early days and what little there is seems mostly forced.

Consider that the Notorious B.I.G. featured but one solitary guest on Ready To Die, the inimitable Redman on the stupendous The What, and Lil Wayne’s latest album I Am Not A Human Being II featured no less than 10 tracks with guest verses. And these were people within the range of Soulja Boy, Gudda Gudda and Juicy fucking J, who are the utter contrast of ‘any good’.

Similarly, does Rick Ross really need to feature people like Wale and that bumbling imbecile Meek Mill on so many songs when they are so inherently awful and no amount of Rozay grunts surrounding their shitty lyrics is going to change that?

The power of the guest verse has shifted from artists helping artists to simply a means to cut down the work of making a traditional album by a huge margin as well as to quench contemporary music fans’ thirst for epic team ups that The Avengers and Watch The Throne have so craftily popularised and exploited.

Nobody asked the question ‘What would it be like if Dr. Dre, Jay-Z AND Rick Ross teamed up‘, but you can bet that it happened because they’re three big names without considering whether it was even a very good idea (it wasn’t) and without making sure that the end result was as outstanding as it could have been (it wasn’t).

Don’t get me wrong. There are still examples of good collaborations that both make sense and are amazing happening today. Jay-Z and Nas quashed their longstanding beef to put out joint track Black Republican in 2006 and it was fantastic. Childish Gambino and Chance The Rapper have nailed on just about everything they’ve teamed up on without sickening me to tears. Kendrick Lamar is this generation’s Eminem, turning absolutely everything he touches, no matter with whom, to gold. The long-awaited collaboration between he and fellow Black Hippy members Ab-Soul, Jay Rock and Schoolboy Q is among the most anticipated albums I’ve ever heard of and it may not even happen.

Kanye might be the master of how guests should be handled though and no album exemplified this more than My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. So many artists from such a varying degree of backgrounds crammed into one album and it never felt crowded once, everyone had a defined role and place and it always felt like Kanye’s album. Other than huge guests like Jay-Z, Elton John and Rihanna, he made room on there for young upstarts like Pusha T and Nicki Minaj to shine. The latter absolutely stole the show on Monster. The most self-referential line comes with her admission ’50k for a verse, no album out’, a subtle acknowledgement that she is an unestablished up and comer, that she is Ye’s guest on this and that this is her chance for a big break. What happened? She broke. Huge.

Giving Drake a lapdance huge.

Point is; when done right, guest verses can be absolutely huge, transcendent, career-altering.

But you have to think before you feat, perhaps even ‘What Would Yeezus Do’, and that just doesn’t happen often enough anymore.