Music is an art form that has universal appeal. For many of us, music is associated with every aspect of our lives. We listen to it all the time, obsess about the artists who create it, write about it a lot and spend our money on gigs, festivals, albums and merchandise. Music is often used to define a decade or a generation and in the past it has also been used to sell cigarettes.

In the mid 1990s, multinational tobacco company British American Tobacco (BAT) decided to tap into that “universal appeal” and use music, specifically dance music, to influence young people to start smoking and to smoke their brand – Lucky Strike.

Anyone who smokes in Australia (or doesn’t for that matter) knows the dull green packaging that is used to brand all cigarettes sold here. Since implementing plain packaging and prohibiting stores from even displaying cigarettes behind the counter, there is no advertising whatsoever, and smoking is often considered an anti-social habit. The government has increased taxes and put extensive limits on the locations in which people are allowed to smoke in an effort to encourage people to stop, including enforcing distances between food areas, doorways and more. The cigarette advertising of the past is a fairly alien concept to us, and seeing cigarettes portrayed as fashionable and attractive in movies and advertisements of previous eras seems like another world entirely.

With increasing restrictions on straightforward advertising in place, marketers in the 1990s had to get creative. Instead of using films, BAT used real people – and real music.

To skirt some of the laws coming into play, while marketing to a key demographic – hip, young people, BAT decided to utilise dance music and the live music scene in London as a marketing tool. They partnered up with longstanding club, and later record label Ministry of Sound to promote their cigarettes to young party-goers. The Ministry of Sound is still hugely popular today, as a club, a tech brand, a source for those longstanding beloved compilation albums, and of course, as one of the foremost dance music labels in the world.

A 2011 report published by the European Journal of Public Health reviewed previously secret tobacco industry documents that outlined BAT’s plans to sell Lucky Strikes using the Ministry of Sound. Everything from promotional images to press releases explaining the campaign strategies are accessible through the article, which explores how the two companies collaborated across the UK, Europe, Asia and beyond.

First, a little history. This type of guerrilla marketing, using the music industry to promote tobacco and develop brand identity and recognition within young adults, started back in the mid 1970s. US company Brown & Williamson began promoting within the live jazz scene in New York, sponsoring New York’s Kool Jazz Festival in 1975 and promoted their menthol cigarettes, which they specifically tailored to African American males. They sponsored the festival because “music is the framework or building block for a deep, emotionally resonating theme … [with dimensions of] nostalgia, reflection of mood, [and] group identification.” The brand hoped that associating with jazz music would bring them credibility and increase the popularity of male menthols. Similarly, Camel launched their Smooth Moves events which involved live music, contests, branded merchandise, games and free cigarette samples.

BAT and Philip Morris similarly sponsored the famed Montreaux Jazz Festivals throughout the 1980s and 1990s, again wanting to associate themselves with the “youthful imagery” and specific musical tastes of the era. As music had, and always will have a universal appeal, the trick then was to make that work to the advantage of the tobacco companies.

While B&W associated itself with jazz in the US, BAT found its niche within the dance music culture in Britain throughout the 1990s.

In the 1990s, bars, clubs, karaoke venues and discos became a “fertile ground for cigarette promotions and events aimed at young adults.” Nightclubs and bars were the ideal places to integrate cigarette brands with the lifestyle, and to ensure that smoking was part of “normal adult life,” starting from a younger age – 18 – 25, the demographic most commonly found in clubs at the time (and still today.)

The Ministry of Sound established itself as a nightclub in 1991 and quickly rose in popularity and fame to the point where it was considered a ‘superclub’ and a brand unto itself. Its image was undeniably cool and many who attended the club were seen as tastemakers and influencers among London’s youth. The basis of the partnership was to link live music events and dance music culture with the Lucky Strike brand.

In their proposed strategy, BAT explained, “If we liaise closely with [discos and bars] and develop a partnership for the promotion of the outlet and our brands, then we should be able to gain control of the music, light show and DJ for the purposes of BAT promotions.”

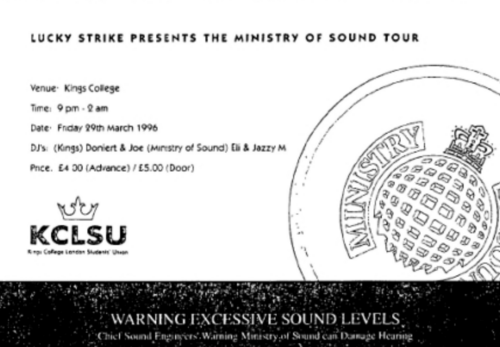

Key events included two massive national Ministry of Sound tours, launched and sponsored by BAT, first kicking off in 1995. The tour visited more than 50 events in various London clubs, bars and student unions, while a second follow-up tour came after the first successful run. A multitude of marketing tools were implemented; this included free cigarette samples, free merchandise giveaways, branded games and advertisements in local magazines. They even brought out a “sampling posse,” essentially an updated version of the ‘cigarette girl,’ and enforced venues to exclusively stock Lucky Strikes – including only stocking vending machines with the brand.

The tours were as overwhelming success. BAT recorded boosts in sales of Lucky Strike after every single event and announced in a UK press release that from “June 1996 – year on year,” they increased sales over 100% as a direct, specific result of the Ministry of Sound tour.

A flyer from a Lucky Strike x Ministry of Sound event at Kings College, London. Image: Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Public Health Association

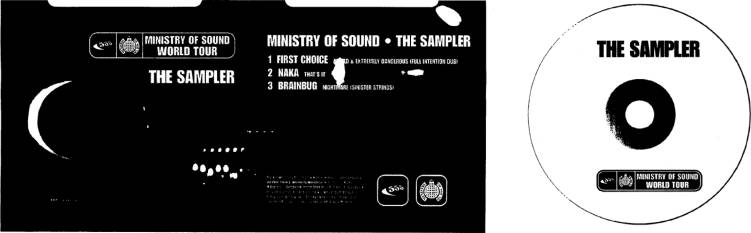

After their success in UK, BAT launched similar campaigns in China and Taiwan with the brand State Express 555. They took the Ministry of Sound event on a world tour that reached as far as Cambodia, Vietnam, Bangladesh, Mauritius and Indonesia among others. During the tour BAT also contracted Ministry of Sound to create merchandise, club culture guides and three-track CDs branded with the 555 logo to hand out at events – on top of just straight up handing out smokes to attendees.

MOS toured throughout Europe, South America, South Africa and beyond, advertising Lucky Strike, 555 or Benson and Hedges depending on the location. In 1998, Lucky Strike was promoted in Russia and Western Europe, while B&H was marketed in Mauritius in 1998 and 1999. The company developed a term to describe the intended demographic: ROCAS – Responsible, Optimistic, Confident and Ambitious Smokers. This was a more specific strategy than other brands, who were looking more broadly at the HORECA industry (Hotels, Restaurants, Catering), by the way.

Other tobacco companies to tap into this relationships included Rothmans in Nigeria and Camel in Argentina. The report talks about one particularly notable point during a travelling disco in Russia, in Novosibirsk, Siberia, where attendees were only able to gain entry to the club if they brought five empty packs of Marlboros with them.

These techniques didn’t finish in the 1990s, nor at nightclubs, for the record. In 2008, an Alicia Keys tour of Indonesia was initially sponsored by Philip Morris International/Sampoerna (PM later withdrew at Keys’ request). A Japanese cigarette company sponsored a music festival in Tanazania in 2009, and BAT and Lucky Strike were still promoting their brand in venues throughout Spain at the same time.

BAT and other tobacco companies used the positive, trend-setting associations and influence of dance music to cultivate brand credibility and brand association among young people to ensure that their cigarettes were an integral part of that culture. Ministry of Sound, and other music events and companies in its wake, had built an identity that represented innovation and exciting, fresh, underground dance music. To associate with this group of people and this culture was a powerful, and for the most part, extremely successful guerrilla marketing tactic at the time.

Similar to the way brands now use Instagram or Facebook to associate themselves with certain lifestyles, ‘influencers’ and social sub-groups, tobacco companies used nightclubs and related music events. These companies capitalise on the knowledge that young people are eager to follow trends and willing to do whatever is deemed cool.

Examples like these demonstrate the importance of the measures taken by Australia to stop tobacco brands exploiting something so precious to sell cigarettes to people.

Source: European Journal of Public Health

Image: Oxford University Press on behalf of the European Public Health Association