The words “break-up album” hold a lot of currency in the world of pop music, but Bob Dylan‘s Blonde on Blonde tells more. It’s romance in its entirety: the giddy heights, the downs and all the ephemeral moments in-between. It draws the listener into an illusionary world where there’s heartbreak, longing, lust and love lurking in every corner.

An undeniable fixation upon romance courses through the album. Surreal and effortlessly cool, it blends bluesy rock sounds with Dylan’s idiosyncratic vocal delivery. Some writers argue that lyrics, while just as meaningful, aren’t poetry in a true sense. If this is so, Dylan is the living exception. The songwriter crams his lyrics with detailed observations while somehow marrying them to melody. Yet unlike letters on a page, there’s also an intimate emotional connection that travels beyond words. Dylan’s music isn’t just heard, it’s felt.

However, to become the elder statesman of rock, Blonde’s Dylan is youthful and impetuous, albeit a little world weary. Paired with his self-titled debut in 1962, Blonde bookends the artist’s meteoric rise to stardom and precedes his mysterious retreat from the public eye two months after the album’s release. Disappearing at his creative peak, the same artist or momentum never truly emerged.

With Blonde, Dylan comes to fully inhabit the jive talking beat junkie, the romantic poet and rock star persona he cultivated with Bringing It All Back Home and Highway 61 Revisited . But it’s by no means an obvious continuation. The album exists in a self-contained world, a standalone statement.

Released May 16, 1966 (although some accounts differ), Blonde on Blonde is an album born of immense pressure. Moving towards the recording sessions, Bob Dylan fans were hungry for new music and subcultural acolytes were readying themselves for messianic revelations. The genesis of the album lays in ideas scrawled within in stolen moments secreted away from a whirlwind of touring commitments, publicity and fan mania. It’s easy to imagine Dylan penning ideas late night in muddled hotel rooms. There’s a cramped sense of atmosphere and an aching feeling of exhaustion that bleeds through from the album’s densely lyrical compositions.

Work began with a lengthy and mostly abortive attempt at recording in New York late in 1965. Retaining only Most Likely You Go Your Way (And I’ll Go Mine) as a finished cut, Dylan relocated to CBS’s Nashville studios in January the following year. Within this new environment, the singer’s scattered ideas were painstakingly repurposed and reimagined. Joined by a portion of his New York entourage, Dylan merged his existing sound with the effortless musical acumen of veteran Nashville session musicians. The end result was a formidable double album, the essence which could never be recreated, although even Dylan himself would later try with Street Legal. It’s perhaps Dylan’s own description that sums the album up like no other can: “The closest I ever got to the sound I hear in my mind was on individual bands in the Blonde on Blonde album. It’s that thin, that wild mercury sound.”

Robert Shelton in his seminal Dylan biography No Direction Home describes Blonde as beginning with a joke and ending with a hymn. The joke is Rainy Day Women #12 & 35. In a world of bi-yearly EPs, teasers, viral marketing and advanced reviews, it’s hard to imagine the impact of Rainy Day Woman #12 and 35. But travel back five decades and inhabit the mind of that diehard Dylan fan. Rushing home from the store, anticipation runs across your thoughts. Your mind flushes with relish for that moment the pin hits the vinyl. Cue wonky marching drums and the demented instrumentation that follows. Dylan knows how to make an entry.

The unconventional track’s semi-live sound plays with expectations. Characteristically abstract lyricisms mix with biblical scripture to form a slow marching subcultural mantra. “Everybody must get stoned,” Dylan giggles amidst the stomping revelry. “They’ll stone when you try to make a book,” he bemoans, slipping in an oblique reference to the poorly received manuscripts of his novel Tarantula.

Pledging My Time and Obviously 5 Believers continue the artist’s jangly blues-rock leanings. Dylan could always project a weathered voice and coarse gravitas beyond his years and these tracks prove no exception. Alongside Just Like A Women, Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat evokes an almost folkloric association with Dylan’s doomed flirtations with Factory girl Edie Sedgwick. The track spits forth venomous cultural commentary, perhaps revealing growing disenchantment and a desire to retreat from the world of celebrity. Temporary Like Achilles drags with constriction, gleefully savouring the failure of a relationship while goading another half to do better. The flirtatious shuffle Absolutely Sweet Marie pulses with energy, bristling with innuendo it serves up memorable Dylanism: “To live outside the law you must be honest.”

Third track Visions of Johanna stands out as a mercurial lyrical masterwork. Love is the central preoccupation. The longing melancholy of Visions was penned following Dylan and Joan Baez’s separation and hints at the latter’s icy dismissal. It’s hard to isolate when exactly Dylan sucks you in. Saturnine lyrics drip with longing, scratchy instrumentals follow a meandering tempo and a suffocating feeling of heartbreak leaks from the chords. The poetic leanings of Dylan’s lyricisms have seldom reached the level of resonance and intricacy they find in the narrative of Louise and Johanna.

Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again captures the spontaneity with which it was composed. While the biggest artists of the day retreated into the studio to create surrealistic productions which could never be created live, Dylan resisted the norm. Ad libs and a few mumbled lyrics add to the ragged charm. The track oscillates between a gamut of emotion; joyous glees, despair, and seething frustration. Strict literal interpretation yields nothing. Dylan conjures an absurdist narrative. But that’s his magic. Intonations, phrasing and animated sonic timbre, make it next to impossible not to picture vivid mental images. “Well, Shakespeare, he’s in the alley/With his pointed shoes and his bells/Speaking to some French girl/Who says she knows me well.” Behind the lyrics there must be a meaning or at least an idea. Bob Dylan knows it, but you’ll never understand it. Yet on reflection you can’t shake the impression that you’ve somehow met him halfway.

Just Like A Woman is one of Dylan’s most divisive works, yet also one of his most commercially successful. Again, it chronicles the breakdown of a relationship. It exists in the irrational mind of a jaded lover. It’s the feeling, not the words, which make the song. A moment of self-righteousness and hubristic denial of self-loathing. It’s akin to blaming another when we will inevitably come to blame ourselves.

I Want You is the songwriter’s take on Top 40 pop. Bob Dylan raps the lyrics of a venomous yet devotional would-be lover. Thematically there’s an insistence and directness which marries perfectly with the on-the-nose nature of power pop. Despite its commercial leanings, the heartfelt narrative strikes a genuine chord.

When The Beatles released Nowhere Man in 1965 it’s ¾ timing, circular lyrical structure, and Lennon’s atypically confessional lyrics were noted as overtly Dylanesque. In Fourth Time Around, Bob returns the favour by adopting a style which mocks Fab Fours’ appropriation in turn. “I never asked for your crutch, now don’t ask for mine,” he levels.

Sad-Eyed Lady of the Lowlands reveals the writer’s total infatuation with new wife Sarah Lowlands. Blonde‘s devotional closing track paints a lyrical portrait of a women stepped in mysticism. Having discreetly married the previous year, Bob Dylan would remain with Lowlands until the pair divorced mid-1977. In Sara on 1975 album Desire, Dylan articulates that he authored Sad-Eyed Lady at the famed Chelsea Hotel. It’s hard not to zero in on lyrics, but the music which underscores the track is also remarkable. Hypnotically building over a minimalistic song structure, you can almost feel the anticipation of the studio musicians wondering if the next chorus will be the last. The track also serves as an antecedent to the heartbroken lyricisms of Desire and Blood on the Tracks over a decade later.

Blonde on Blonde captures Bob Dylan’s craft at one of its finest moments. Redefining the role of the singer-songwriter and the very fabric of popular culture with prophetic ease, the album serves to remind us why Dylan remains an exalted musical figure. Fans and critics may be divided over which (if any) of Dylan’s cuts is his best, but it wouldn’t be difficult to tender the idea Blonde on Blonde stands out as the greatest. Tramp, troubadour, and entertainer, the album showcases Bob Dylan at his best.

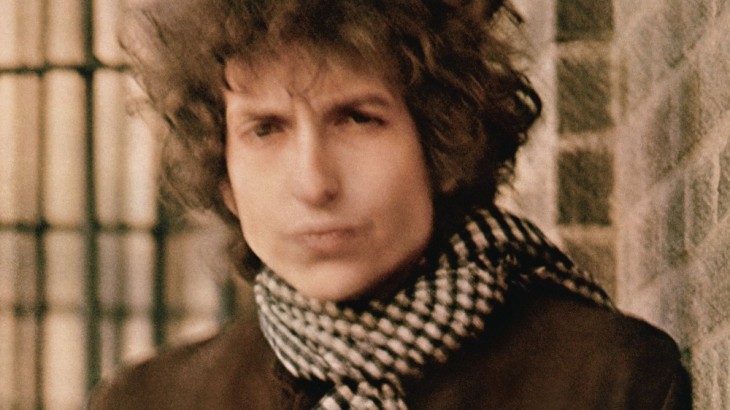

Image: Rolling Stone