“Won’t it be strange when we’re all fully grown?”

Different Class turned 20 about a month ago. I often reflect on Britpop’s halcyon days, circa 1995, as a golden era of my cherished memories as a music fan. Even though it isn’t a memory of mine at all. I wasn’t even two years old when Roll With It was battling it out with Country House for the prized Number One spot. But neither Oasis (after their inevitable reconciliation and Glastonbury headline slot) nor even Blur (despite their admittedly excellent 2015 return) will ever be what Pulp were.

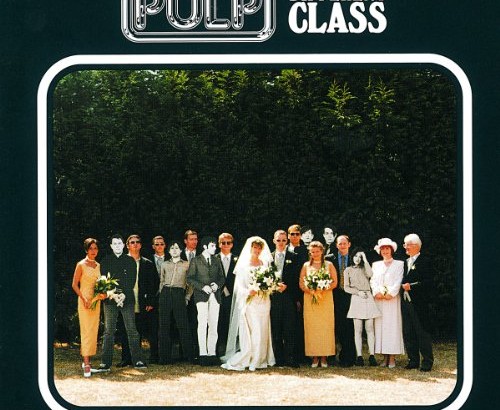

Different Class was the band’s critical and commercial peak. It is a very good album in the musical sense: the pop songwriting is tasteful and memorable, and the production (particularly in the couple of reissues since released) is crisp and clear. But in a broader sense, it is much more than very good: for many, including myself, Different Class belongs in the pantheon of music that transcends the sum of its parts.

Like OK Computer represented the schizo-paranoia of the new millennium, and To Pimp a Butterfly will come to represent the artistic realisation of the Black Lives Matter movement, Different Class now embodies something far less glamorous: middle-class, suburban life. The only life I’ve ever known.

“I want to sleep with common people like you.

Well what else could I do? I said… I’ll see what I can do.”

Common People is the one you’ve heard. There is little argument against it being one of the best songs of all time, frankly, so I’m not going to launch into a diatribe. But it’s worth noting the song’s myth is still evolving even now. The couplet above is particularly imprinted in my memory. Cocker, listening to his Greek muse assure him that she wants to be poor like everyone else, does the musical equivalent of ‘breaking the fourth wall’. And of course it would be revealed the Greek girl who had a ‘thirst for knowledge’ and ‘studied sculpture at St. Martin’s College’ happened to be the wife of the ill-fated former Greek finance minister, Yanis Varoufakis. With Cocker, so it goes.

Humour is often at the crux of a good Pulp song, as it is with Common People. But the finance minister’s wife isn’t the only real character, and Cocker is a master of the art of distilling the ‘bitter’ from the ‘sweet’. Disco 2000, on which Cocker literally boogies as he recounts the story of his first love, introduces us to Deborah (whose name never suited her). The song, all power-chord synths and bustling dancefloor rhythms, is magnificent in its own right. But the song is now tinged with sadness; its subject, a mental health worker named Deborah Bone, passed away at the end of last year.

“You see you should take me seriously; very seriously indeed.

Cause I’ve been sleeping with your wife for the past sixteen weeks,

smoking your cigarettes, drinking your brandy,

messing up the bed that you chose together.

And in all that time I just wanted you to come home unexpectedly one afternoon,

and catch us at it in the front room.

I can’t help it, I was dragged up

my favourite parks are carparks

grass is something you smoke

birds are something you shag

take your year in Provence

and stick it up your ass.”

The half-spoken I Spy is the purist’s honorary favourite. It sees Cocker at his most demented and vengeful. Given the overtly truthful nature of the songs on Different Class, the song is disarming in its willingness to lay bare all of Cocker’s darkest insecurities, and leads us down the all too familiar self-obsessed mythologising we are prone to: “The crowd gasp at Cocker’s masterful control of the bicycle, skilfully avoiding the dog turd outside the corner shop/ Imagining a blue plaque, above the place I first ever touched a girl’s chest”.

On a later album, Jarvis Cocker would profess that he isn’t Jesus, though he has the same initials. Converts to the church of Different Class would tend to argue otherwise. For here, Cocker’s everyman presents himself as a sort of middle-class messiah. He is louche; risqué; often downright seedy. On I Spy he is hateful, but like Walter White after him, we are helpless to avert our eyes.

“Check your lucky numbers,

That much money could drag you under, oh

What’s the point in being rich

if you can’t think what to do with it

‘Cos you’re so bleeding thick?”

The album’s conception was curious, because Cocker wrote most of it after Common People exploded. He was dizzy with the prospect that he’d finally made it. Now was his chance to disseminate his bigger ideas. And that sentiment above, from Mis-Shapes, basks in Cocker’s pubescent superiority complex. Sure, they can beat us up because they’re stronger, but we’re smarter, so we’ll have our day, one day. It’s unapologetically petulant, but it’s also a proper rallying cry for all the ‘misfits’. Cocker himself foresaw it on the albums other big hit, Sorted for E’s and Wizz: it would rightly be shouted by 20,000 people standing in a field in Hampshire.

“How the hell did you get here: semi-naked in somebody else’s room?

I’d give my whole life just to see you standing there/ Only in your underwear”

Cocker is scarcely able to conceal his excited gasps as he yelps the phrase on Underwear. The more vividly perverse lyrics border on bad taste, but the point of the album is that Cocker transcends his position as merely a mouthpiece for the masses; on Different Class, he embodies the guilty, ugly, jealous thoughts of modern suburban life. And if you haven’t thought something like that about a special someone, you’re probably lying.

An earlier song, Pencil Skirt, examines possibly the same sexual encounter. “I’ll be around when he’s not in town/ I’ll show you how you’re doing it wrong/ I really love it when they tell you to stop / Oh it’s turning me on!” By this time Cocker has established himself as a wretch and a scoundrel of the highest order. The problem is, Cocker is probably you, semi-naked in somebody else’s room you didn’t really want to be in.

“I wrote the song two hours before we met.

I didn’t know your name or what you looked like yet.

Oh I could have stayed at home and gone to bed.

I could have gone to see a film instead.

You might have changed your mind and seen your friends.

Life could have been very different but then,

something changed.”

But for all the unfiltered insights into Cocker’s loathsome suburbia, here you will find a gold mine of equally, gloriously romantic sentiments. On album highlight Something Changed. Cocker boils down all the giddy heights of falling in love with someone into a simple analysis of a single moment. Perhaps we all have an unattainable, faraway Greek goddess to spend our days thinking about, but on Something Changed, all that cinematic bullshit is at its most real. If I was to get married, I would want this song to play during the first dance.

Perhaps the comparison I made at the start of this review was misguided. Different Class doesn’t have the intellectual credibility of Radiohead’s best effort, and it certainly lacks the moral credibility of Kendrick’s opus. But what I’m trying to say, I suppose, is that the ostensibly singular Cocker is also the most relatable character I’ve heard on a record.

Different Class is the creeping guilt after a grimy one night stand. It’s the hopes and fears of a generation going nowhere in particular. Most importantly, it’s timeless. Lately, to my horror, I’ve been spending a lot of time questioning if I’m a good person or not. Different Class is just another story of another life. An unflinching, unapologetic study into those tiny, ephemeral moments in time that make us who we are.

Like Cocker, we are all (mostly) fuck-ups, making it up as we go. Different Class, with all its rueful goodbyes and winking hellos, is the not-so-delicate reminder we’re all fucking up together.